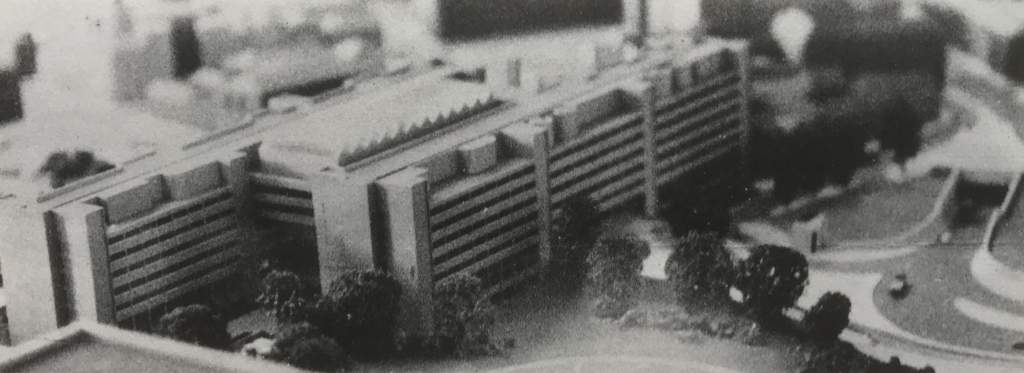

A model of the proposed Civic Centre, showing its location with the Mersey tunnel entrance on the right and St John’s Gardens in the foreground.

By the 1960s Liverpool corporation was operating from 49 different buildings, dotted around the city. Many of the staff worked in antiquated offices, often in crowded conditions, and this provided the cue (or a least the excuse) for an over-ambitious project to bring all corporation activity under one roof.

It wasn’t only about the comfort and convenience of officials, though. Graeme Shankland, the planning consultant who first suggested it, wanted a building that would also bring prestige to the city — “something more than just a particularly monumental office block”. Local politicians lapped up the idea and a photo from 1967 shows the two most most important council figures — Conservative leader Sir Harold Macdonald Steward and Labour leader Bill Sefton — together with the architect admiring a model that looked alarmingly like a multi-storey car park.

To general surprise Sefton hailed it as “the greatest experiment in democracy any city has attempted”. One of the ideas behind the design was to make local government less remote and more accessible in its dealings with the public. “Social amenities” included in the plans would draw people into the building, thus presumably allowing them to rub shoulders with councillors and officials.

By that stage estimates of the cost had reached £17m — at a time when the government in Westminster had set a £10m limit. This meant the plans had to be scaled back. The “social” element was hastily chopped out and what had originally been known as the “Civic and Social Centre” was now simply the “Civic Centre” — in other words the sort of “monumental office block” that Shankland had been hoping to avoid.

Labour and Conservative groups on the City Council both supported the project and only the Liberals opposed it — with the result that it got less critical scrutiny than it deserved. The Daily Post and Echo, meanwhile, had no interest in stirring up controversy since they stood to benefit financially.

Nevertheless, there were several strong arguments against the project. One was about the cost and whether the money spent would be a wise use of financial resources and whether comfortable offices for officials were really so important when thousands of Liverpudlians were still living in unfit council homes. As Jim Hunter, a local architect and opponent of the scheme, observed: “At least Corporation employees are able to walk out at 4.45 p.m.”

Some people questioned the entire plan, on the grounds that centralising corporation offices in a single building was a move in the wrong direction. Slum clearance meant inner-city dwellers were moving out to the suburbs and several corporation several departments were already decentralising by setting up neighbourhood offices to make themselves more accessible to people in different areas.

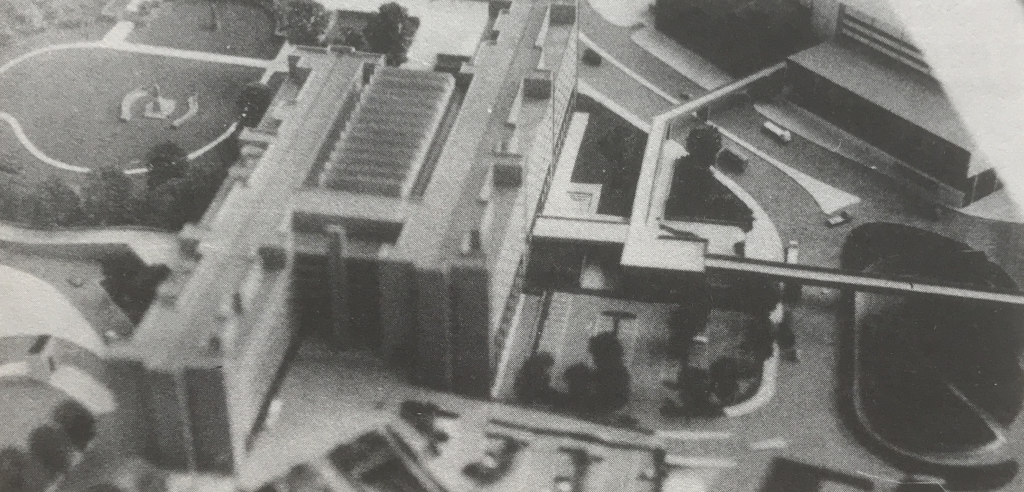

The Civic Centre model from a different angle, with St John’s Gardens in the upper left of the photo. The two footbridges that were supposed to connect with the Civic Centre can be seen on the right.

‘A bloody awful building’

Most contentious of all, though, was the design produced by Colin St John Wilson, better known as the architect of the British Library in London. Its intended location was a prime site overshadowing St John’s Gardens and facing the neo-classical buildings of William Brown Street and St George’s Hall on the other side — so the question was whether the proposed design for a bronze-tinted monstrosity would make a suitable neighbour for those architectural gems.

One person who thought it wouldn’t was Francis “Jim” Amos, the chief planning officer. In private he was said to have described it as “a bloody awful building”, though in public he was more circumspect. On two occasions the Royal Fine Arts Commission invited him to speak in defence of the building but he turned down both invitations, blaming “other engagements”.

By 1973, ten years after the project was first announced, almost £3m had been spent but the only sign of building work was two footbridges leading to the non-existent Civic Centre (their construction had cost £227,000 and one of them ended abruptly in mid-air above a car park).

Fees for the architect and consultants amounted to around £1 million and, in the view of the city’s chief architect, Jim Boddy, St John Wilson had been overpaid for his work on the Civic Centre. Boddy pointed out that while the building was being designed, the RIBA had reduced architects’ fees from 6% to 5.5% on projects costing more than £1.75 million. Paying at the new rate would have thousands but St John Wilson objected and the Town Clerk supported him, saying 6% was what had been agreed.

In this photo the Civic Centre building is blurred to focus on the neo-classical buildings in William Brown Street which are almost blotted out.

A further £1,489,000 had been spent buying up properties on the huge 13-acre site. Of all the buildings bought to make way for the Civic Centre, the largest was the Post & Echo building — a ramshackle warren of offices with a printing works at the rear. By 1970 its roof was leaking and on wet days copies of the Echo were used to soak up drips in the composing room on the top floor. In short, the company wanted to be rid of it. They were already looking for a site for a new building and the old one clearly wasn’t worth very much, assuming someone could be found to buy it.

Luckily, though, there was a willing buyer in the shape of Liverpool corporation. Initial plans for the Civic Centre showed the Post & Echo building standing in the way. This meant the corporation would not only have to purchase the property in order to demolish it but would also have to compensate the Post & Echo for “disturbance” caused by the move to new premises — a move that the company had already chosen to make regardless of the plans for the Civic Centre.

For a while, though, the deal hung in the balance. Subsequent cost-cutting on the Civic Centre design and the removal of “social amenities” reduced the amount of land that would be needed — with the result that demolition of the Post & Echo building wasn’t strictly necessary. However, the view from the planning department was that the Civic Centre would have a “better setting” if the Post & Echo building was pulled down. After a period of haggling, the corporation generously coughed up £730,000 for the building and resulting “disturbance” (plus £18,000 legal fees).

Despite all this expenditure the Civic Centre did not yet have planning permission and in 1972, when the corporation submitted an application, the government ordered a public inquiry. This was the first — and last — chance for the public to ask awkward questions about the Civic Centre, knowing the corporation would have to answer them. Presenting the corporation’s case at the inquiry, Senior Assistant Town Clerk Ken Wilson was alternately patronising and arrogant when cross-examining objectors from community groups. He suggested only unthinking people could be against the scheme, that they might be well-meaning, but they didn’t have the knowledge, the experience or the ability to criticise.

One opponent of the scheme, architect Jim Hunter, complained that artists’ images giving an unfavourable impression of the proposed building were not among those shown to the inquiry – to which St John Wilson replied that there were too many pictures to show and some had to be left out. In response to complaints that it would cast a huge shadow over St John’s Gardens, the architect produced a diagram showing the extent of the shadow “at noon on the summer solstice” (which was the time when the shadow would actually be at its smallest).

Amos, the planning chief, made a reluctant appearance at the inquiry, giving a strictly factual analysis of Liverpool corporation’s need for modern offices. This didn’t satisfy the objectors and Amos was later recalled in his capacity as a qualified architect, to give his “personal view” of the design. Choosing his words carefully, he said he thought it was too dominating and maybe a better solution could be found.

The government inspector, whose name – Ken Dodds — caused some amusement in Liverpool, then left to consider whether planning permission should be granted. His decision, a few months later, stunned the project’s supporters: permission was refused.

“The proposed building, because of its alignment, overpowering bulk, scale and severe uncompromising regularity, would be oppressive and tend to overwhelm the elegant assembly of neo-classical buildings in their setting in the conservation area,” Dodds wrote in his report.

The corporation could have tried again with a different design, but instead the project was quietly abandoned. As the inspector pointed out, it would be ridiculous to go ahead when the whole structure of local government was about to be changed.

0 Comments