“Radio Free Liverpool” was one of several clandestine broadcasters on Merseyside in the 1970s. The enthusiasts behind these pirate stations played a cat-and-mouse game with the authorities who often confiscated their home-made transmitters

by BRIAN WHITAKER

In the 1950s, as more and more people spent their evenings watching television, there were widespread predictions that TV would kill off radio. By the 1960s, though, radio was becoming popular again, especially among youngsters. The chief reason for this was the introduction of transistor radios. They were small, portable and affordable – just the thing for teenagers to listen to at night under the bedclothes.

Although there was no law to stop anyone starting up a newspaper, broadcasting in Britain had been strictly controlled since its inception and the BBC was the only legal broadcaster. Its monopoly over television ended in 1955 with the creation of ITV but its radio monopoly continued into the 1960s.

For music, the main alternative to the BBC was Radio Luxembourg, broadcasting to the UK from mainland Europe, though reception was often poor.

A more serious challenge to the BBC came in 1964 when Radio Caroline began broadcasting pop music from a ship in the North Sea. Its boast was that it played the sort of music the public wanted rather than what the record companies wanted them to hear.

The authorities struck back in 1967 with the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act which made it illegal to supply offshore radio stations or advertise with them. As a concession to the pirate stations’ listeners the BBC launched Radio One as a pop music channel and hired several of the pirate DJs.

That didn’t satisfy everyone and, in parallel with the emergence of the alternative press, there were various radio enthusiasts broadcasting on illegal (often home-made) transmitters and mainly playing requests from listeners. Their range was usually only a few miles and they were engaged in a constant cat-and-mouse game with the authorities.

The Radio Caroline shop

In Liverpool, this activity revolved around a tiny run-down shop on Prescot Street which didn’t appear to sell anything but had a sign above its window saying “Radio Caroline”. I had often noticed it while passing on a bus — which, as I later discovered, was why an electrical engineer called Ronnie Dee had decided to rent it. The shop was on a busy road and next to a bus stop serving several routes. “If the traffic lights were on red, sometimes six or more buses would be backed up the street, one behind the other,” he later recalled. With so many people passing by, he reasoned, the Radio Caroline shop was bound to get noticed.

Music ahoy: Ronnie Dee on the tape decks of the pirate ship Mi Amigo

Dee used it as a base for his travelling disco, the Radio Caroline Roadshow, having dressed up his tape decks to look like Caroline’s ship, the Mi Amigo. Dee showed me his equipment, reminisced about the great days of Radio Caroline and introduced me to several other enthusiasts when I visited one evening in the 1970s.

They denied doing any illicit broadcasting themselves but were clearly well-informed about the exploits of “friends” who did. They were probably the only people in Liverpool who valued the city’s tower blocks, because setting up a transmitter at the top of one increased its range. It also meant they could keep watch for police arriving in the street below — which gave them enough time to switch off the transmitter and disappear.

On Merseyside, the most prominent of the illicit stations was Radio Free Liverpool which began broadcasting in 1969 and probably continued until 1976. The Free press reported on its activities on two pages in Issue 9 (here and here).

Further information

The DX Archive website has a page on Radio Free Liverpool which includes some audio clips, a list of known pirate stations on Merseyside and Ronnie Dee’s memoirs. It also has couple of newsletters from the Cheshire Free Radio Organisation (CFRO) about the station’s activities and the authorities’ attempts to stop them (see below).

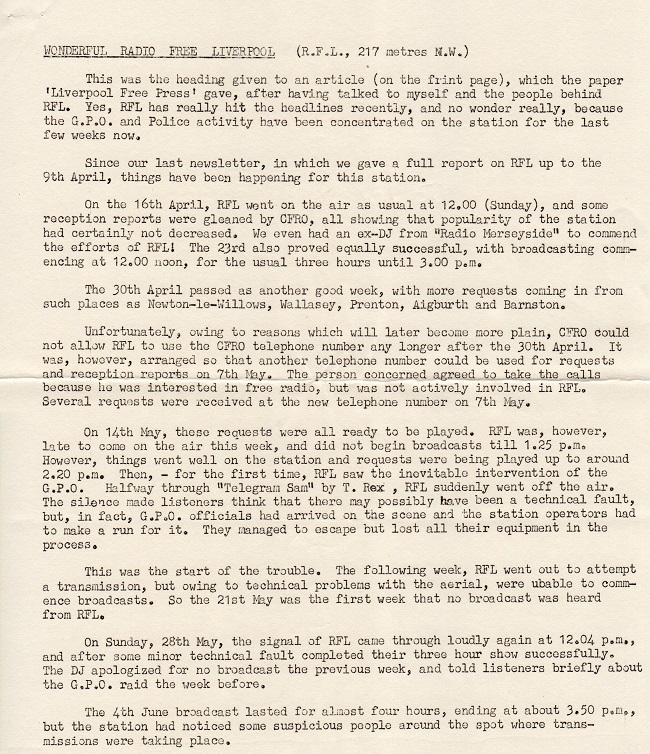

From the CFRO newsletter, May 1972

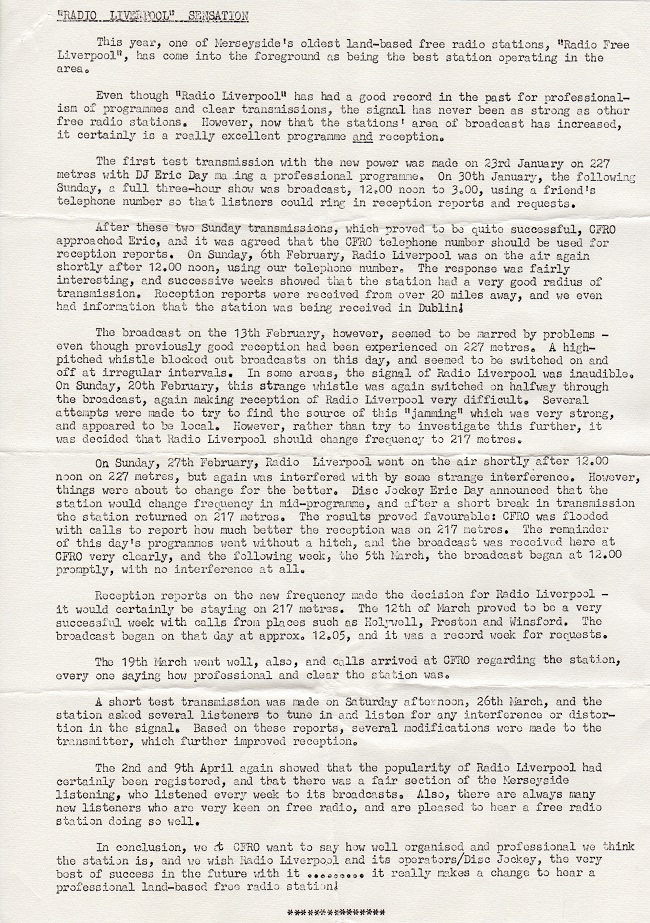

From the CFRO newsletter, August 1972 (first page)

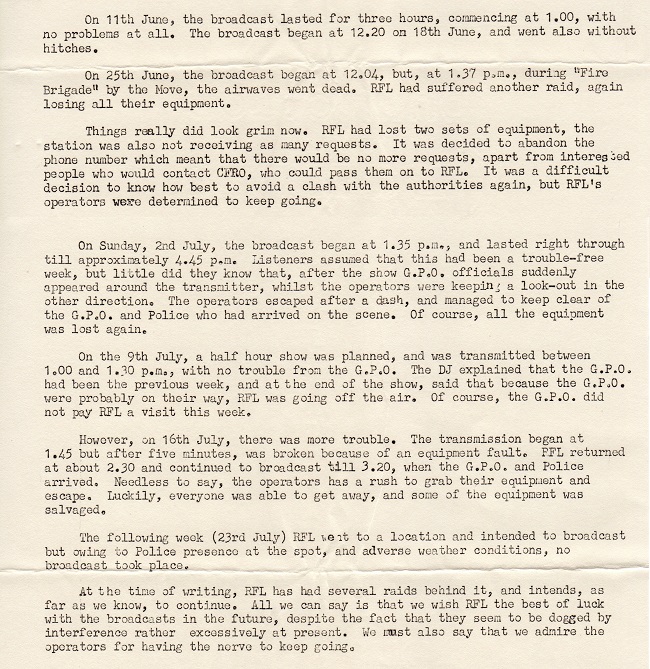

From the CFRO newsletter, August 1972 (second page)

0 Comments