Activists campaigning against Britain’s military presence in Northern Ireland faced surveillance and prosecution during the 1970s

In August 1972 the Liverpool Daily Post held a competition for boys aged 13–16. The ten lucky winners would spend an “action packed” day with the army in Wiltshire that would include rides in tanks. Competitors were given a list of eight possible reasons for joining the army — and asked to place them in order of preference.

By an unfortunate coincidence the announcement of this contest appeared on a page reporting that the hundredth British soldier had died in Northern Ireland — a youngster from Kirkby who had joined up because he was unemployed. There were complaints at the time that the army was focusing its recruitment efforts in areas of high unemployment. In Kirkby, a councillor accused the military of “taking advantage because they know that young lads here are desperate for money”.

Liverpool Free Press, issue 10, page 3 (Sept-Oct 1972)

Military recruiters also enjoyed some privileges that were not available to other potential employers. In 1974, for instance, it emerged that they didn’t have to pay for a stand at the Liverpool Show — unlike other exhibitors. The explanation given was they also provided “entertainment” in the form of bass bands, parachutists and displays of military equipment. Around the same time, the army put on a “show” at Bootle Sports Stadium which it followed up with a recruiting advert in the local Formby Times:

“As soldiers we train hard, work hard, play hard. And enjoy good pay, good prospects, and a good life into the bargain. “You could have all of this too, if you joined us for just 3 years. And, if you chose a 6 or 9 year stay, your money would be even higher …”

Liverpool’s Director of Recreation later asked the council’s permission “to investigate the possibility of a military tattoo being held on Wavertree Playground in September 1975”. However, there was significant disquiet among councillors: they were evenly divided over whether to call for a report and it was only approved on the chair’s casting vote. Around the same time, the military were excluded from the Skelmersdale Show after two previous occasions when assurances that they would not use the show for recruiting had been ignored.

Calls to withdraw troops

The most prominent organisation campaigning against Britain’s military presence in Northern Ireland was the Troops Out Movement, founded in 1973. A second organisation was the British Withdrawal from Northern Ireland Campaign (BWNIC). Troops Out activists tended to be Marxists and/or supporters of Irish republicanism while BWNIC was mainly rooted in pacifism.

The authorities clearly regarded both organisations as dangerous. Troops Out was infiltrated by an undercover police officer who, over several years, rose to become a significant figure in the movement. BWNIC, meanwhile, faced legal harassment. By 1973 there were a few signs of discontent among soldiers serving in Northern Ireland and some of them were leaving the army (or trying to leave). A report in the Liverpool Free Press quoted one who had left:

“I’m not against being a soldier. I would be willing to fight to defend this country against an invader … But what is happening in Ireland is all wrong. Some of my friends have been killed there. I keep asking myself — what did they die for?”

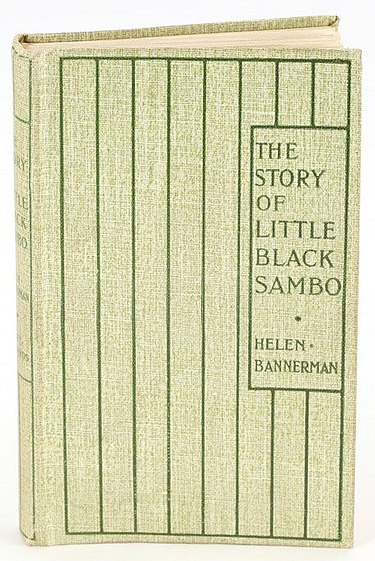

The article went on to outline various legal ways of leaving the armed forces — and some of the difficulties. It also said that “at least twelve” soldiers posted to Northern Ireland had been granted political asylum in Sweden and gave details of the asylum process. The article was mostly based on a leaflet circulated by BWNIC under the heading “Some Information for British Soldiers”.

Liverpool Free Press, issue 14, page 2 (Oct/Nov 1973)

In 1974 Pat Arrowsmith, a veteran peace campaigner and co-founder of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, was arrested for handing out the leaflets at an army base and sentenced to 18 months in jail for offences under the controversial Incitement to Disaffection Act of 1934. Section One of the Act says:

“If any person maliciously and advisedly endeavors to seduce any member of His Majesty’s forces from his duty or allegiance to His Majesty, he shall be guilty of an offence under this Act.”

In the light of Arrowsmith’s conviction BWNIC revised the wording of its leaflet and changed the heading to say “Some Information for Discontented Soldiers” — on the grounds that it was not trying to “seduce” soldiers into leaving but simply providing information for those who already wanted to leave. This is the revised leaflet …

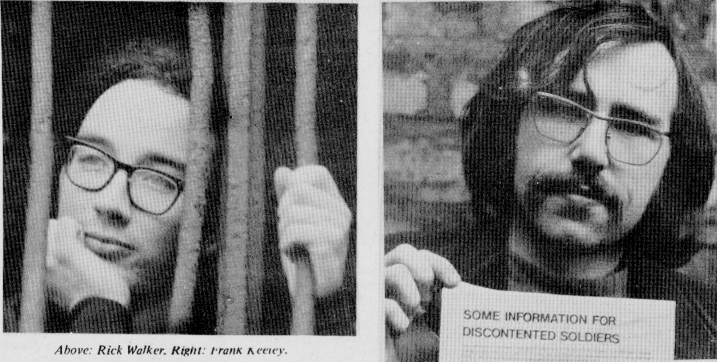

In August 1974 — three months after Arrowsmith’s conviction — two 21-year-old Liverpool men, Rick Walker and Frank Keeley, handed out copies of the revised leaflet near army barracks in Oswestry, Shropshire. The following October, police arrived at Walker’s home and arrested him. He was then taken to London to be charged under the Incitement to Disaffection Act.

Keeley, having heard that a warrant was out for his arrest, travelled to London of his own accord and gave himself up. Meanwhile, police searched his parents’ home in Kirkby, telling his mother that he was “mixed up with Communists” who would soon start “using him to carry parcel bombs”.

Altogether, 14 activists were arrested in different parts of the country. They were initially charged under the Incitement to Disaffection Act, as had happened with Pat Arrowsmith, but more serious charges of “conspiring” to seduce troops from their allegiance were added later (even though some of the alleged conspirators had never actually met).

Accused: Rick Walker (left) and Frank Keeley

Tampering with the mail

While on bail awaiting trial Keeley noticed strange things happening with his mail. “Since the middle of January, at least five letters sent to Frank have failed to arrive,” the Free Press reported. “One was from his solicitor, one from the Defence Group in London and another from the Defence Group in Manchester. Two letters from his cousin have also vanished mysteriously in the post.

“A tax rebate did arrive, though the envelope had been ripped open. It had been stuck together again with sellotape and a scribbled note said: ‘Envelope damaged by sorter 6/2/75’.”

To investigate this further, the Free Press decided to send him a test letter. He wasn’t told what would be in it but was given instructions to bring it back unopened if/when it arrived. Inside an ordinary white envelope was a piece of undeveloped photographic film in light-proof wrapping. If the letter had been unopened, the film could be developed and a picture would appear. If it had been opened, the image would turn out black. If someone realised the trick and substituted fresh film, there would be no picture. The Free Press reported:

“We posted the letter — First Class — at 4.30 pm on February 13. It did not arrive next day, but on February 15 Frank Keeley got two letters.

“One was our own white envelope. Close scrutiny showed it had been slit open at one end and skilfully resealed … The film was inside, but the light-proof bag had disappeared.

“The other letter was a large brown envelope with a smudged postmark … Inside was the missing light-proof bag, and clipped to the bag were two pieces of paper.

“One was a photocopy of what looked like an amateurish attempt to create an official letter-head. It had the Royal Coat of Arms and the words ʽMinistry of Intelligence Department Six’.”

The other piece of paper had a handwritten message in capitals saying: “I wonder if you’ll get the same as Daly? He was too hot as well. Still that’s your funeral”. On the back it said; “Two of your ‘friends’ have blood on their hands. Have they told you?” The mention of a “too hot” man called Daly was puzzling but after some research the Free Press concluded it was probably a reference to Tim Daly, a poet who had been jailed several years earlier for trying to burn down the Imperial War Museum.

Acquitted in 90 minutes

The conspiracy trial cost the government about £250,000 and a Special Branch team spent almost a year gathering what evidence they could. The court sat for 51 days but in the end it took the jury only 90 minutes to deliver “Not Guilty” verdicts on all the accused.

The trial included some memorable comments from Judge Neil McKinnon. When asked whether he pleaded guilty or not guilty, one defendant, Michael Westcott (aka “Tenebris Light”), told the court: “I plead for peace in a world of war, love in a world of hate, free speech for all, and an end to politically motivated trials in this country.” To this, the judge replied: “I shall have to have a medical report on you if you are not careful”. Their exchange was reproduced in large type on the cover of Peace News and was also turned into a poster. At another point in the trial Judge McKinnon described “human rights” as “an emotive expression used in international documents”.

The Peace News cover

In the celebrations that followed the verdicts, defendants and jurors met informally and talked to each other for the first time. Rick Walker gave his impressions of their meeting in an article for the Free Press headed “Information from discontented jurors“. Activists then stepped up their leafleting and in 1975 nine of them, including two from Liverpool, were arrested (see photos) outside a recruitment office in Preston and charged with obstruction. All were later acquitted after a three-day hearing in the magistrates’ court.

FURTHER INFORMATION

- The Bishopsgate Institute in London has a 42-box archive of press clippings, correspondence, press releases, photographs, videos and ephemera produced by the Troops Out Movement between 1973 and 2011.

- In 2021 there was a public inquiry into police surveillance and infiltration of legitimate political groups, including the Troops Out Movement over a 40-year period from 1968.

0 Comments