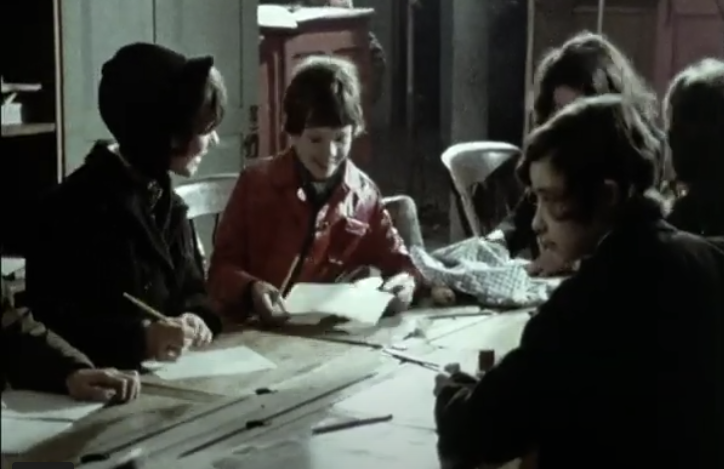

Children at work in the Free School, early 1970s

In the summer of 1971 residents of Liverpool’s Vauxhall area received a leaflet announcing plans for a new local school — plans that were little short of revolutionary. Scotland Road Free School, the leaflet said, would have no headmaster or hierarchy and lessons would not be compulsory: “The onus will be on the teacher to stimulate the children sufficiently to attend …”

In one of the most deprived parts of the city the Free School offered a radical alternative to the state education system, and it came at a time when critics of conventional teaching were advocating new ways of learning and a different kind of relationship between teachers and those they taught.

A few months earlier there had been much controversy over a book by two Danish teachers containing advice for school students. Known as The Little Red Schoolbook, it was provocatively designed to resemble the little red book of thoughts from Mao Zedung that demonstrators had waved during the Chinese Cultural Revolution and much of its content was decidedly subversive. Among other things, it informed children that …

- Many teachers have never done anything apart from teaching and may not know much about life outside school. Many of them come from a different social background to their pupils.

- Teachers don’t teach what you really need to know, but rather the things that other people think you ought to know.

- Exams often ask the wrong questions. They may show what you’ve learnt parrot-fashion or had knocked into you but they rarely show whether you can think for yourself and find things out for yourself.

In Britain, another section of the book — which assured students that masturbation is normal and harmless — resulted in the publisher being fined for obscenity.

Experimenting with alternatives

This was also a time when many people saw no hope of change through tinkering with existing systems and instead sought to create new ones based on different principles. There were numerous small-scale experiments in “alternative” ways of living and working, such as communes and workers’ cooperatives. “We aim to live out in the present, as far as possible, the future of freedom and cooperation,” one manifesto said.

The Scotland Road Free School was part of this, as its leaflet explained:

“It is felt that the state system in contemplating change considers only innocuous reforms which do not question the full structure. We are obliged therefore to step outside the system in order to best demonstrate the feasibility and fulfilment of the free school ideal.”

It added, optimistically:

“Having achieved this demonstration we are sure that society will enforce the adoption of the free school idea by the state system …”

Attempting to bring democracy into the classroom wasn’t so much a new idea as the revival of an old one. Back in 1921, A S Neill had established Summerhill, an independent (fee-charging) school in Suffolk where decisions were taken collectively. Staff and students all had a vote, and the students could choose which classes, if any, they would attend.

In 1960, when Neill’s book, “Summerhill: a Radical Approach to Child Rearing”, was published in the US it sparked a wave of interest there, turning Neill into a celebrity across the Atlantic and resulting in a spate of new American schools claiming to be run on Summerhill lines.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s free schools also began springing up in Britain’s cities. The first one opened in Notting Hill, London, in 1966 but there were others in Bristol, Birmingham, Glasgow, Manchester, Leeds, Nottingham, Manchester and Brighton as well as Liverpool, though none of them lasted very long.

Breaking out

The founders of the Scotland Road school were two Liverpool teachers, John Ord and Bill Murphy, who had decided to break out of the state system.

The school opened in September 1971 with just five children, rising to 16 by the end of the first term. The number peaked later around 50.

During its short existence the school operated from four different locations, none of which were really suitable: the Victoria Settlement, the Everton Red Triangle Club, St Benedict’s Church Hall and a disused school building off Stanley Road which was owned by the council.

Among media visitors during the school’s first term was a film crew from Thames Television for a programme titled “Should education be compulsory?” Broadcast in December 1971, it contrasted the Free School’s approach with the government’s emphasis on discipline and formalised teaching, together with its plans to extend compulsory education by raising the school-leaving age from 15 to 16.

John Ord: Free School children “know what they want to do”

In the programme, co-founder John Ord hit back at claims the Free School students were simply messing about and wasting time. The real time-wasters were state schools, he said:

“The first three-quarters of an hour [in state schools] is nothing — going into assembly — stand up, sit down — filing off into rooms — stand up, sit down — get your books out …

“We’re far more efficient than that. When a child sits down at these desks [in the Free School] it is for a definite reason. They know what they want to do, they know where they are at. They say: ‘I want to do this. Come and show me.’ It’s important, it’s powerful.”

A group of adults, interviewed for the programme in a pub nearby, talked enthusiastically about the Free School. One man said he had read about A S Neill and the Summerhill school and was “very impressed with their ideals”.

Children attending the Scotland Road school were enthusiastic too, according to parents. “They love it. They can’t go quick enough to school,” one mother said. Another noted the difference between her son, Jim, attending the Free School, and her other children in “ordinary” schools. “To the kids in the ordinary school, lessons are just nothing. It’s just the same old thing from nine to four, history, geography.” Jim, on the other hand, would come home from the Free School eager to tell her what he had been doing there.

The adults in the pub were far from enamoured with the state system, partly due to a suspicion that in areas like Scotland Road the purpose of state education was not to improve the children’s prospects but to limit their expectations. The state system, one man said, was “geared to a standard where they are only allowed to learn so much”. The few youngsters in the area who went on to college were mocked and regarded as freaks, he said. “When I was a kid they were called ‘college puddings’.”

Broader horizons

Taking the children out on visits was a routine part of the Free School’s activities and it created opportunities for informal teaching: a visit to a ruined castle in Wales, for example, became an outdoor history lesson. The trips also widened the children’s horizons, giving them a glimpse of life beyond Scotland Road — and for some it was the first time they had seen a farm. A few of the destinations, though, were not the sort typically visited by school groups. One trip took the children to the Fisher Bendix factory in Kirkby which had been occupied by its workers. Another visit was to Clay Cross in Derbyshire where the local authority was disobeying government instructions to raise council house rents.

The school trips not only showed the children how people in other parts of the country lived but also how people in other parts of the country viewed the Free School children.

“They were aware that they were seen differently,” former teacher Marilyn Scrider recalled. “We went into some very pleasant rural areas where people took one look at the Liverpool kids and were terrified. We went to Worcester and it was incredible. We saw people battening down hatches as we came. We just looked so different and the kids looked so different. We went to Glasgow and the kids made some threatening gestures out of the coach at Glasgow kids and a brick came promptly and hit the coach. The kids were quiet the rest of that trip.”

Fortunately for the school, it was able to keep travel costs down through a connection with Liverpool Community Transport, which owned two elderly double-decker buses and a coach that could be used for social outings by people in the area as well as the Free School.

Free School reunion

Twenty years later — and sixteen years after the Free School closed — the BBC tracked down some of its former students and staff for a documentary. The 44-minute programme looked at what happened to them and how, with hindsight, they felt about the project.

[A video of the programme is available on YouTube and in the discussion that follows numbers in brackets refer to relevant points in the video.]

The BBC found a third of the Free School’s ex-students were unemployed (which was not untypical for the area) but almost as many were working as managers or running their own business. Three had died, one was in jail and the rest were manual workers.

One former student, Tony, had got a job with an engineering firm after leaving the Free School but it promptly went bust. After a spell doing community work he took an apprenticeship in hairdressing and by 1992 was running his own barber shop (27.52).

Another student, Maria, had gone straight to work at Littlewoods pools after leaving the Free School and later worked abroad as an au pair. When the BBC found her she was running a small catering business (24:34).

“I think I would have been an entirely different person if I’d stayed in a state school, a normal school,” she said. The Free School “made you think” and the pupil-teacher relationship was different. “In the Free School you were all treated as equal” (7:54).

By the time of the documentary, some ex-students had school-age children of their own. Tony, asked whether he would have liked to send his three children to the Free School, said: “If there was one going now, I don’t know. I’d let them choose themselves” (29:06).

Another parent, Alice, said: “I’d have to go and find out all about the school … but I think no.” Her 10-year-old daughter was doing well at a Catholic school and seemed happy there (20:58).

Maria, meanwhile, had made a more surprising choice by sending her children to private secondary schools. She explained that she had wanted her son to go to an all-boys Church of England school but it wouldn’t accept him because his mother was Catholic. He had then taken an entrance exam for Liverpool College, passed and got an assisted place there. She later sent her daughter to a private school too (25:16).

Maria’s sister Diane — also a former Free School student — had made a similar decision. “I think the education system now is rubbish and private education is really the only other alternative,” she said. “To start with, you are getting this choice. You are not just being herded along … it’s your own choice. I think that was what appealed to me about the Free School as well” (25:43).

Make your own rules

Without compulsory lessons or a formal curriculum, the school often gave the impression of having no rules. According to Ord, though, the point was that it could make its own decisions about what rules to have, and what to put in them. “A free school is a place that operates in the way that the people in it want it to operate,” he said (4.35). “You want to make rules? You make rules. And when you find out that the rules don’t work, you change them. It’s a constantly changing thing.”

This could be a difficult adjustment for children and teachers alike. Ord, having taught in the state system for three years, sometimes had to restrain himself from slipping back into the old ways: “I still had a residue of it left in me,” he said (6.08), “so when you see a kid sitting around talking or just reading you think ‘My God! Why isn’t he doing something?’ ”

The Free School’s function, Ord explained (5:58), was to guide the children through “the kind of process that you go through when you first accept freedom” … “the main problem of freedom is accepting it — because accepting what it really means is a frightening thing”. This often led the Free School’s children to demand more rules and more discipline, and in Ord’s view they were trying to retreat into the security they had felt previously in the state system.

Summerhill school has operated on similar principles for more than a century: freedom brings responsibility and is not to be confused with licence. “You are free to go to lessons, or stay away, because that is your own personal business, but you cannot play your drum kit at four in the morning because it would keep other people awake,” its website says.

Summerhill also claims to have more rules than any other school in the country — 250 of them, including a rule that doors must be opened by hand, not kicked open with feet, and football boots mustn’t be washed in the bathrooms.

In 1999 Summerhill was threatened with closure. After government inspectors expressed concern about its non-compulsory lessons education minister David Blunkett issued a notice of complaint, giving the school six months to comply with its demands. Summerhill challenged this at a tribunal and secured an agreement that future inspections should take the school’s “philosophy and values” into account.

Summerhill survives because — unlike the Scotland Road Free School — there are enough parents willing and able to pay. The current (2025) fees for non-boarding students range from £7,680 to £15,375 plus VAT per year, depending on the child’s age. The Scotland Road school, on the other hand, couldn’t expect parents to pay fees and the local education authority was reluctant to chip in — so money was a constant problem.

Free School classroom

Struggling for funds

The Free School’s teachers were unpaid (some lived on the dole) and it also had voluntary helpers from the local community. Financially, it relied heavily on the proceeds from jumble sales and raffles, plus donations sent through the post. Andy Churchill, the school’s former administrator, recalled worrying about its unpaid heating bill and opening the post every morning in the hope of finding donations — which in those days came mainly in the form of one-pound and five-pound notes. Once the money had been counted an argument broke out over whether to pay the heating bill or spend it on taking the children to Formby beach (12.36).

The Free School had asked the council’s education department for help with books, furniture, school meals and premises but a meeting of the schools sub-committee in October 1971 turned down its request after the Director of Education advised that there were already “enough maintained schools in the area”.

That decision was partly reversed a couple of weeks later at a meeting of the full education committee following a surprise intervention by Lord Beaumont of Whitley, the Liberal Party’s spokesperson on education. The meeting agreed to give the school equipment and allow free use of playing fields and swimming baths but made no decision on contributing to school meals or providing premises.

A dumping ground for truants

One argument in favour of financial support was that when children transferred from state schools to the Free School the education authority benefited by having fewer children to provide for. Another argument was that the Free School could also help to relieve the authority’s truancy problem.

One early example was the case of a boy who had been persistently absenting himself from the Archbishop Whiteside school. The education department warned his parents that if he didn’t start attending he would have to be detained in an approved school but, according to the Liverpool Free Press, they suggested to his parents that sending him to the Free School might be an alternative solution . His parents took the hint and the Free School accepted him, thus saving the trouble and expense of keeping him in an approved school.

The Free School’s policy was to accept any child who wished to attend, and this eventually contributed to its downfall. As time went on, it was increasingly seen as a convenient dumping ground for “problem” children.

“Towards the end, that was one of the things that made it unworkable,” former teacher Marilyn Scrider said. “More and more different kids were coming — kids you didn’t know — and it was difficult for the kids who’d been there a while and who felt at home and who felt comfortable.” It was also difficult for the adults to work with new children all the time (17.13).

Former student Tony said: “The likes of the kids we started getting into the school — you couldn’t really take them anywhere because they were that disruptive. They caused trouble, they’d be going out stealing things. There were truants and petty thieves — that kind of thing. I left after 18 months and it was beginning to go downhill then” (18:13).

End of the road

After four years of struggles to survive, the Free School’s fate was sealed. Co-founder Bill Murphy said: “The last few days were grim because we had no resources. We had a building we couldn’t afford to pay for, we had very few people working there at that particular point, we had no money and so one really felt that the thing was slowly but surely coming to an end. That was depressing because when we had to close it we let those kids down. I still feel that now. There’s a failure there still which hangs over me” (18:40).

Murphy later emigrated to New Zealand where he worked on a community housing project. Co-founder John Ord remained in Liverpool but state schools were unwilling to accept him back. He worked in a variety of jobs — on the buses, in a car factory and with a cleaning firm — before being allowed to teach again. He also went into local politics, serving on the council during its confrontation with the Thatcher government over the city’s budget and was one of the councillors eventually disqualified. He died in 2021 aged 76.

FURTHER INFORMATION

PHOTOS OF THE FREE SCHOOL:

Liverpool Free School 1971

A collection of 46 images by John Walmsley

Janine Wiedel Photo Library also has a collection

VIDEOS ABOUT THE FREE SCHOOL:

Liverpool Free School: Should education be compulsory?

Thames Television, 1971

Lessons In Freedom: The Scotland Road Free School

BBC2 Education Special, 1992

John Ord talks about freedom at Scotland Road school

BBC, 20 October 2014

ADDITIONAL READING:

We don’t need to be schooled to learn

Archived article from an anarchist magazine discussing various experiments in libertarian education, including Scotland Road Free School.

Organise! #63 – Winter 2004

The anarchic experimental schools of the 1970s

By Tom de Castella

BBC News Magazine, 21 October 2014

What is the rationale behind free schools?

A large number of “free schools” have been established since 2010 but the concept iss different. They are funded by the government and called “free” because they are independently run. This article explains them.

BBC, 9 March 2015

Scotland Road Free School [1971-1974]

ED 172/596/3

The National Archives, Kew

0 Comments