Historian RACHEL COLLETT traces the growth of the Women’s Liberation Movement through the 1970s and 1980s. On Merseyside its initial hub was the Women’s Centre in Seel Street and activists focused mainly on reproductive healthcare in the face of strong local opposition to abortion and contraception. They also tackled sexism in children’s fairy stories and often joined forces with other campaigning groups: on one occasion feminists marched alongside striking dustmen.

The British Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) emerged rapidly in the late 1960s, involving thousands of women across the country in an exciting and radical attempt to achieve women’s equality in both personal and public life. While sharing broader goals with early twentieth-century feminists, Women’s Liberation activists in the 1970s wanted ‘revolution, not reform’, focusing not just on legislation, but on overhauling entire structures of society and culture. As activist Lynne Segal reflected, ‘every aspect of women’s lives was being reassessed through a feminist lens.’

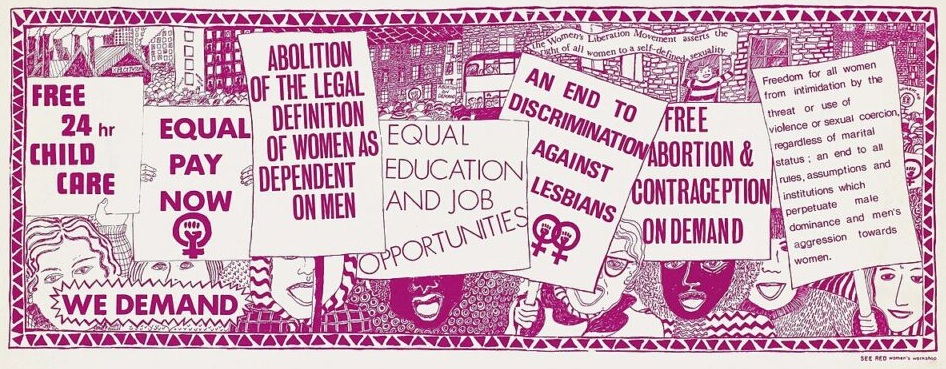

Contrary to previous political movements, the WLM was not a singular organised campaign with leaders and hierarchies. Instead, feminists in Britain adopted a decentralised structure to encompass a multitude of grassroots women’s groups, single issue campaigns, women’s centres, refuges, bookshops, creches, magazines and more. These were loosely connected through annual national conferences and seven public-facing demands:

The first four were discussed at the first WLM conference in Oxford, 1970

1. Equal pay now

2. Equal education and job opportunities

3. Free contraception and abortion on demand

4. Free 24 hour nurseries

Added at the sixth WLM conference in Edinburgh, 1974:

5. Financial and legal independence

6. And end to all discrimination against lesbians; and a woman’s right to define her own sexuality

Added at the tenth and final WLM conference in Birmingham, 1978:

7. Freedom from intimidation by threat or use of violence or sexual coercion regardless of marital status; an end to the laws, assumptions and institutions which perpetuate male dominance and aggression to women

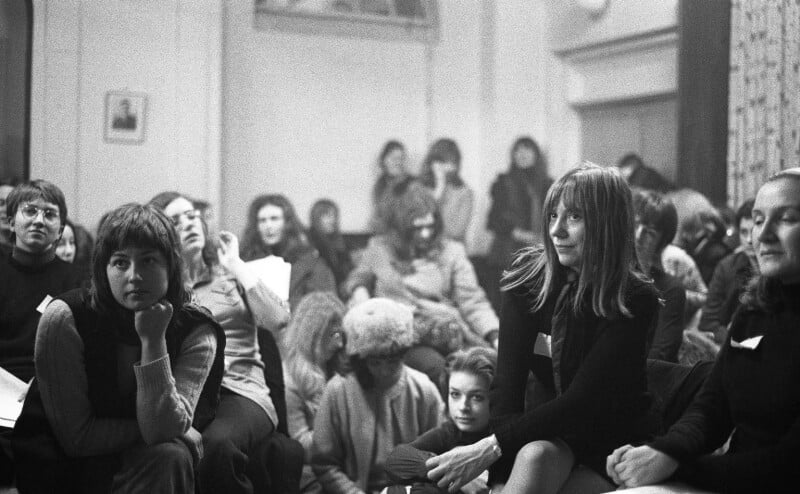

The first WLM conference, Oxford, 1970, with Sheila Rowbotham in the foreground on the right.

Women’s growing dissatisfaction

As the familiar narrative goes, second-wave feminism emerged in reaction to the contradictory position of women in post-war Britain and elsewhere. Higher living standards, better access to education, and a wave of liberal legislation granted women similar freedoms to men, raising their confidence and expectations. More young women than ever before were leaving home, going to university, having sex, and participating in the flourishing 1960s countercultures and New Left politics.

Yet, many experienced a conflict between expectations and (a lack of) opportunities. Despite social and cultural changes, women found themselves largely excluded from liberationist discourses and ‘permissiveness’ in the 1960s. Upon leaving university, many were also faced not with exciting careers and independence, but with unchanged expectations of marriage, motherhood, and housework. Alienated by these unfulfilled promises, a new generation of women emerged. Many sensed that there was more to life, but were unable to articulate discontent without the language of women’s liberation.

In the United States, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) described this as the ‘problem without a name’, exposing the myth of the happy and fulfilled housewife as a fabrication of domestic propaganda and consumerism. This, she argued, encouraged women to be passive, dependent, and left them isolated in the suburbs. The publication was a catalyst for second-wave feminism in the United States, providing the vocabulary for women to analyse their lives and voice dissatisfaction with the constraints of post-war femininity.

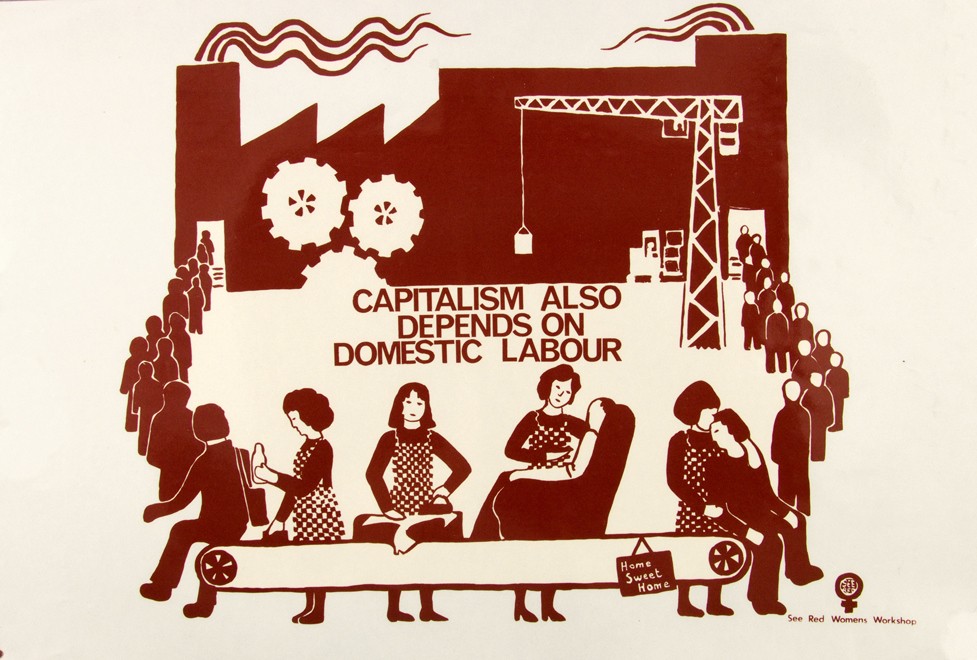

This politicisation of women’s personal and everyday lives was an important part of Women’s Liberation politics. Influential feminist texts like Pat Mainardi’s The Politics of Housework (1970), Anne Koedt’s The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm (1968), and Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics (1970) built on Friedan’s work, highlighting how issues such as sex, relationships, abortion, childcare, and the division of household labour were not merely private problems, but deeply political facets of an oppressive system that required collective solutions. These texts were read and discussed by women across the Atlantic, providing key inspiration for the emergence of the WLM in Britain.

A key point of reference was Carol Hanisch’s essay The Personal is Political (1969), which made the explicit connection between personal experience and larger social and political structures. In the essay, Hanisch urged women to overcome feelings of failure, isolation, or self-blame arising from dissatisfaction. To confront these issues, she advocated for intimate consciousness-raising groups, which allowed women to talk freely about individual problems in a safe, non-judgmental space. Discussions revealed common frustrations and enabled women to draw collective political conclusions and develop intimate bonds of sisterhood, as the basis for practical action.

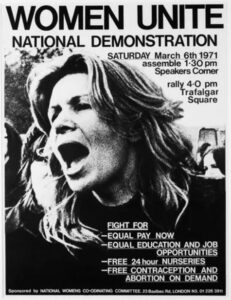

Poster for the first WLM march, 6 March 1971.

Women’s Liberation and leftist politics in Britain

This process was quickly picked up and adopted by women in Britain. Yet, despite sharing aims, texts, and structures of organising with the US movement, British feminism was not simply imported but had its own independent beginnings in the late 1960s. While the American WLM was rooted in civil rights and student politics, many historians have argued that the British movement emerged ‘out of socialism’, in critical dialogue with the country’s broader left radicalism.

A new mood of militancy in Britain’s strong labour movement sparked iconic protests led by working-class women in their communities. In 1968, feminists were inspired by women’s struggle for fishing trawler safety in Hull and striking Ford machinists in Dagenham and Halewood, Liverpool. The latter dispute, in particular, led to the founding of the National Joint Action Campaign Committee for Women’s Equal Rights and was a key influence in passing the Equal Pay Act 1970. Working-class women’s activism had a formative influence on the emerging WLM, helping shape a strong socialist-feminist undercurrent that has distinguished the British movement from its American counterpart in various historical accounts.

This characterisation was also rooted in women’s experiences within left-wing politics in the 1960s. Many were inspired by student politics, drawing influence from the radical challenge to authority and the revolutionary fervour of May 1968. Feminists had also been active in the peace movement, the Communist Party and Labour Party Young Socialists, as well as various New Left groups such as the International Socialists and International Marxist Group, where they gained confidence and political experience. Through involvement with these groups, women inherited a Marxist analysis, particularly taking inspiration from the New Left’s emphasis on cultural politics as well as economics.

Yet, the WLM in Britain also emerged in reaction to this political legacy. Many women felt marginalised by the persistent sexism of male comrades who believed women’s equality should be deferred until after the revolution. Tired of being relegated to making tea and licking stamps, feminists developed an autonomous movement that sought not to replicate the formal, hierarchical structures of male-dominated left politics and avoided open political affiliation. This was not a rejection of men, but a way for women to transform social and economic gender relations alongside male comrades, combining critiques of capitalism and patriarchy.

The first Women’s Liberation conference at Ruskin College, Oxford in 1970, which has gained almost mythic status in WLM histories, particularly highlights this connection to existing socialist networks. The organisers included socialist-feminist activist intellectuals Sheila Rowbotham and Sally Alexander, who had been laughed out of the radical History Workshop group for proposing women’s history discussions. The resulting meeting became the first of the WLM’s national conferences, bringing together over 400 women, 60 children, and 40 men from emerging feminist groups across the UK. A year later, on 6 March 1971, the first WLM demonstrations were held in London, Liverpool, and Scotland to publicise the movement’s demands and represent a co-ordinated, unified feminist presence to the public and press.

By September 1971, over 150 loosely connected autonomous groups existed in 45 locations across Britain, each forging local feminist movements rooted in their distinct contexts, identities, and communities. While the national movement had many unifying aspects, focusing on these regional differences allows us to understand the diversity of Women’s Liberation at the grassroots.

Forging local feminism on Merseyside

On Merseyside, the movement began in late 1969 with a handful of informal meetings at Princes Park Mansions, in a flat belonging to town planner and housing activist Catherine Meredith. Other early members included trainee speech therapist Anne Neville, teacher Marge Ben-Tovim, social worker Pat Wilson, and Sheila Abdullah, a health activist and radical GP. This initial group, many of whom were already friends and neighbours, had come together to discuss their shared interest in the burgeoning WLM and what it aimed to achieve.

Over the next few months, more meetings and discussions quickly followed, and the group invited representatives from the Women’s Equal Rights Campaign and London Women’s Liberation Workshop to learn more. They held their first formal meeting soon after, on 12 February 1970, and, two weeks later, several members attended the first Women’s Liberation conference in Oxford (along with two men and two children).

Strong, emotional bonds of sisterhood were forged through the group’s intimate early meetings and discussions, which allowed them to work out collective interests and priorities for campaigning. This formed the foundation of the Merseyside Women’s Liberation Movement (MWLM). Yet, as many members of the initial group were not local to Liverpool, they were also eager to understand the local context and frame their activism to reflect the city and its people, as well as their own interests. The MWLM’s local feminist identity thus emerged as distinctly socialist-feminist and community-minded.

While the MWLM was part of a wider national (and international) movement, early members decided that their first and foremost concern would be ‘direct action in [their] own locality’. They aimed to support and involve local women as a kind of feminist advisory service, and focused on tackling ‘the most pressing injustices’ and ‘local inadequacies’ affecting the whole community. To do so, different campaign groups were established and the MWLM formulated its own set of demands in 1970, building on the existing four national demands:

1. Equal pay for equal work

2. Equal job opportunities and training facilities

3. Equal educational opportunities

4. Equal legal and social status and responsibilities

5. State nurseries and nursery schools available for every child

6. Sex education in schools

7. Free contraception under the NHS

8. Implementation of the Abortion Act within the NHS

9. A shorter working week and shared housework now*

*Added in 1971

The loose structure of the WLM in Britain gave local groups the freedom to interpret national debates, discussions, and demands in diverse ways, meaning they could shape feminist identities according to local women’s needs. In Merseyside, as elsewhere, various national campaigns gained more traction locally, and often played out in different ways.

From the outset, women’s reproductive healthcare formed a major site of feminist activism in response to stark local disparities in abortion and contraception provision in Liverpool. Despite legislative advances since the 1960s, the city was reported as the hardest place in the country to get an NHS abortion, with only 39% of local abortions performed on the NHS. Stemming largely from its Irish Catholic culture and deeply entrenched sexism, Liverpool was a stronghold of medical and religious opposition, and became described as a ‘city against abortion’.

Poster for a National Abortion Campaign demonstration in Liverpool.

This situation prompted a specific local focus on women’s healthcare, which was also influenced by the medical backgrounds of several key MWLM members. GP Sheila Abdullah was a passionate defender of abortion rights and, alongside other sympathetic doctors like Cyril Taylor, used her practice as a site of activism to educate and advocate for women’s health. Her professional expertise gave credibility to the campaign in Liverpool and helped establish several early feminist initiatives, including free pregnancy testing, contraception demonstrations, and educational pamphlets.

Alongside later activists like Dr Katy Gardner and Linda Pepper, Sheila’s passionate energy was important in sustaining women’s health as a key feminist priority throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Feminists were galvanised by national struggles against the White (1975), Benyon (1976), and Corrie (1979) bills, as well as the ongoing local campaign for an out-patient daycare abortion unit, action around defending the Women’s Hospital, and the establishment of Liverpool Abortion Support Service.

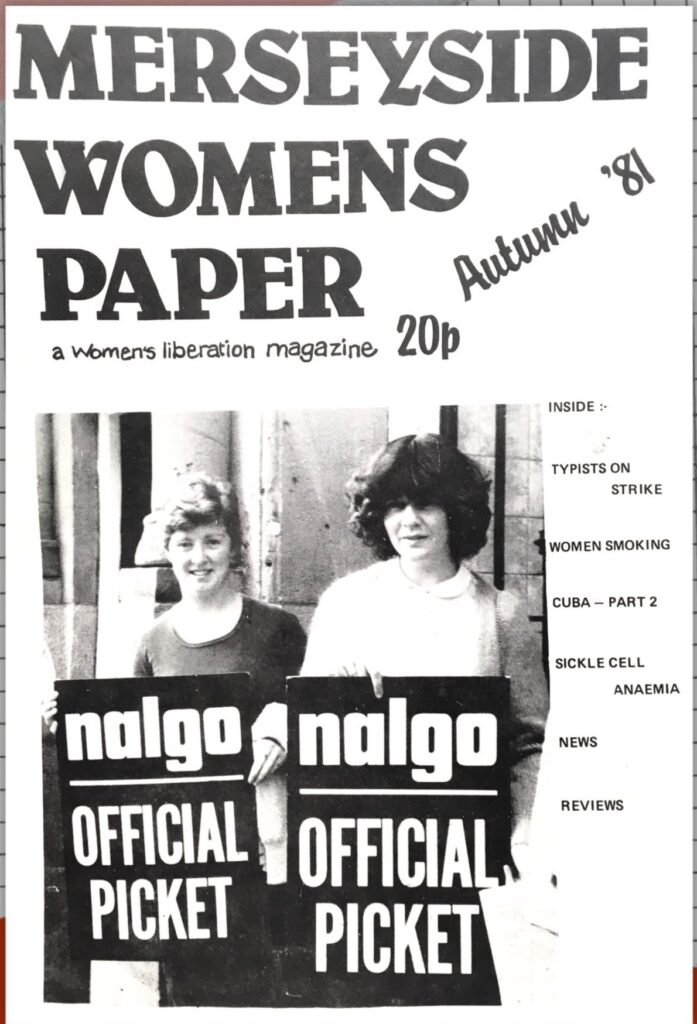

As the Merseyside abortion and contraception campaign shows, much of the MWLM’s early activities were concerned with raising public awareness and reaching out to ordinary women with practical information and support. Alongside public marches, protests, and street campaigning, feminists in Liverpool engaged with the media to promote their ideas and establish the movement locally. Members appeared on local radio programmes, and articles about the MWLM featured in mainstream local newspapers like the Liverpool Echo and Daily Post, as well as alternative left-wing publications such as Openings and the Liverpool Free Press. They also created their own means of communication in the form of a MWLM newsletter, and later on, Merseyside Women’s Paper, both of which provide important insight into the diverse range of feminist activities in the city.

This outward-looking approach also meant that MWLM members were keen to engage with existing women’s groups and left organisations, seeing their feminism as part of a broader movement. In the early 1970s, activists spoke about Women’s Liberation at local branch meetings of the Labour Party and more traditional women’s groups such as the National Housewives Register, or National Association of Women’s Clubs. They also made contact with younger generations, giving educational talks in schools and creating alternative anti-sexist fairy stories for children. These outreach efforts had important consequences, allowing feminist ideas to spread into multiple spaces and prompting the formation of wider solidarity networks in the city.

Linking up with other groups also sparked surprising collaborations. One early example was the unlikely solidarity between MWLM feminists and striking dustmen, who led a campaign for council workers’ wage increases in October 1970. The women suggested a joint march to show solidarity between all low-paid workers. The resulting demonstration saw thirty feminists march side by side with over a hundred dustmen and their wives. While the dustmen carried MWLM placards, the feminists carried dustbins, which they emptied on the steps of Liverpool Town Hall in protest. Examples like this demonstrate how, at least on a local level, Women’s Liberation activism often overlapped and connected with a myriad of different groups in the fight for gender equality.

As a result of outreach endeavours, by March 1971, the MWLM had grown into a large umbrella organisation encompassing several local groups and campaigns spread across the city, with a rapidly growing membership of over ninety women. This prompted the need for a more defined structure for greater productivity and to better facilitate a plurality of opinions and experiences. While retaining some centralised organisation through large general meetings and existing single-issue campaigns, the MWLM split into separate district groups for L8 and L17, Newsham Park area, University of Liverpool, and an autonomous Wirral group. This was unusually structured for local WLM groups. Spatially, it helped spread Women’s Liberation across Liverpool, ensuring the MWLM was not concentrated in one area and facilitating the development of multiple feminist identities in the city.

Expanding a network: new spaces … and obstacles

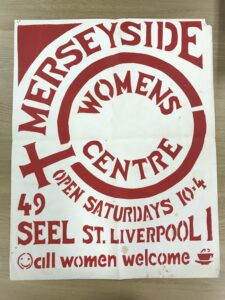

The expansion of the movement also prompted the development of further feminist spaces in Liverpool. In late 1973, the first Merseyside Women’s Centre opened at 49 Seel Street in the city centre. In the early 1970s, the building was originally leased from the council by a group of activists associated with the Scotland Road Free School. As the free school ended in 1972, the men gradually moved out, and the women were joined by other young feminists who were involved in the MWLM. The group consisted of Nina Houghton, Naomi Frisch, Sue Atherley, Mary Weir, Marianne Sawyer, who was involved in housing co-operatives, and Sue Cartledge, who worked alongside Catherine Meredith in the council’s planning department. This expertise and experience with housing was crucial in acquiring and refurbishing the space as a women-only commune and women’s centre.

Number 49 Seel Street quickly became a key feminist space in the city. In Merseyside, as in other towns and cities, the women’s centre became the focal point for local feminist activism and communication, operating as an information and advice centre, library, meeting space, and an informal refuge for vulnerable women. Similarly to later experiments of the 1980s (like the Merseyside Trade Union, Unemployed, and Community Resource Centre on Hardman Street), the Merseyside Women’s Centre was an important space for both feminists and women outside the movement to socialise, access help and support, and tentatively explore collective politics. Symbolically, it also acted as physical evidence of a powerful and tangible feminist movement existing within the city, representing the transformation of everyday urban spaces for political uses.

The Seel Street centre closed in 1977 due to problems with finances, logistics, and difficult internal dynamics. But this did not mark the end of the MWLM. Local feminism continued to flourish in different spaces, including Sunnyside (where the Seel Street commune moved to in 1975), News from Nowhere bookshop, and a new women’s centre established at the Rialto Community Centre in 1978. Like the national movement, the MWLM experienced a widening and diversification at this time. While some historians have characterised the late 1970s as a time of turmoil, tension, and fragmentation for the WLM, it also saw an influx of younger women, different campaigns, and a broader spectrum of ideas and perspectives.

A protest by Liverpool Black Sisters, 1980s

Yet, the MWLM struggled to navigate this diversification. A plurality of ideas and experiences provoked numerous tensions and disagreements from the mid-1970s, over issues concerning class, sexuality, and separatism. One particular area of difficulty was the relationships between Black and white feminists, which were more strained in Liverpool than in other parts of the country. White feminists in the MWLM failed to make meaningful links with the Black community, leading to the establishment of an entirely separate movement of Black feminism in the city, led by groups like Liverpool Black Sisters.

It is important to remember that the WLM was not the only women’s movement of the period, but part of a wider ‘second-wave’ that was fought on many fronts. Alongside WLM groups, women organised in trade unions, tenants groups, political parties, and community groups. Sometimes, as with Black women’s groups, these networks were isolated and distinct from the MWLM. However, in many cases, they did converge around various campaigns, particularly those focused on women’s healthcare, housing, and community action. Collaboration between feminists in groups such as the MWLM and Big Flame and working-class tenants in places like Kirkby and Netherley, for example, resulted in long-lasting networks of solidarity.

These broader left solidarities were especially important in the 1980s as Liverpool entered a difficult decade. The painful experience of riots, deindustrialisation, mass employment and public sector cuts – coupled with Thatcher’s ‘managed decline’ of the city – forced a reconsideration of feminist priorities and strategies as part of a wider militant left in Merseyside and beyond.

* * *

Rachel Collett is a historian of radical Liverpool. Her PhD research focuses on the Merseyside Women’s Liberation Movement from 1969 to the 1990s.

For more on this, see:

- ‘Ruling the dancefloor, organising at the bookshop: News from Nowhere and the fun of 70s feminism’, The Liverpool Post, 7 March 2023.

- ‘Socialist-feminist revival in the Merseyside Women’s Liberation Movement: new priorities, strategies, spaces and solidarities after 1978’, in E. Smith and D. Frost (eds), In Solidarity, Under Suspicion: The British far left from 1956 (Manchester University Press, forthcoming 2025)

- Liverpool Black Sisters doing it for themselves

Kay Jones, National Museums Liverpool, 22 July 2020

0 Comments