These were the opening words of a children’s story by Enid Blyton, originally published in 1937. It was still popular in 1972 when, amid growing concern about gang fights on the city’s streets, Liverpool Community Relations Council (CRC) set up a working group to look at the ways race was portrayed in books for children.

The spring of 1972 had brought frequent clashes between black and white youngsters which flared up again in August, culminating in several nights of violence in the Falkner Place area of Toxteth. The following year, police detained almost 100 young people, both black and white, during some particularly heavy barrages of bottles and bricks between the gangs around Sussex Gardens. Police were also called to Paddington Comprehensive to separate children of different races.

In the light of that, it was relevant to ask what the city’s schools were doing to prepare youngsters for life in a multi-racial society. The House of Commons Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration decided to investigate and the Local Education Authority responded with a report based on a questionnaire it had sent to every school in the city. The Community Relations Council submitted a separate report which included the findings of its research into children’s books.

“If black people are always seen in unfavourable images, both black and white children will be conditioned to think of black people as not being capable, reliable or intelligent. It will particularly affect the black child’s image of himself as someone of worth,” the CRC’s report warned. “There is a necessity for black children to have role models with which they can identify and find fulfilment. Almost all the books we reviewed from schools, and many others recently written, failed on that ground.”

The working group began by borrowing a selection of history and geography books from local schools — and were immediately struck by how old and outdated they were. “Many books in regular use in school were written in the 30s and 40s, during the time that Britain had colonies,” their report said. “They reflect attitudes prevailing during those times.”

Newer publications were not always better, they added. “Some of our monitoring team attended a recent exhibition of books for schools in Liverpool. We found, side by side with some excellent books, many which were biased and [we] wrote to the Education Publishers Association indicating our concern about them.”

Happy cotton-pickers

One of the older books examined was Work in Other Lands by Edna Walter, originally published in 1935 and reprinted in 1960 with its content largely unchanged. Describing life on cotton plantations in the United States, the book said:

“Except when there is so much work in the cotton fields that they have to go and help their mothers and fathers, the ‘piccaninnies’ or darkies children go to school. The planter looks very carefully after his darkies and even sees that they take their medicine when they are ill …

“The darkies who grow cotton in the ‘cotton states’ of Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia are happy people with few cares … Long years ago many of the darkies were slaves, working on the plantations. Even then, very many of them were happy, for they are lighthearted, easy-going people.”

Cheerful cotton-pickers could also be found “crooning their songs” in Geography at the Drapers by Florence West, a schoolbook about textiles published in the 1940s or early 1950s, which the CRC described as hopelessly out of date. While there was no doubt that some black people were still living and working on the cotton plantations, the report said, “what is to be doubted is that they are ‘crooning their songs as they work’. They are more likely to be taking part in bus boycotts, and voter registration campaigns. What is even more certain is that they will object very much to being called ‘dark skinned Negroes’. There is no explanation as to why the work on the plantation is done mainly by ‘black people, men, women and children’.”

The report added that the book gave “no indication of the terrible bitterness, wars and slavery involved in the growth of cotton nor the awful misery of the conditions of the language of cotton workers who refused to work the cotton from the southern states until the slaves were free.”

Many of the books examined treated Africa as a single entity, ignoring its diversity, and most “failed to show Asian, African and South American countries as having towns, cities, manufacturing industries or any worthwhile technological developments”.

Loincloths in the jungle

Some books, such as This is Your Neighbour (published in 1967), perpetuated an image of black people living in primitive conditions. The only Africans shown were living in the Kalahari desert while the only South Americans were in the jungle wearing loincloths. The book also informed children:

“Many aborigines are in fact very clever people. Some of them have become doctors, parsons, teachers and artists. Natives like this often live in towns and cities. They have accepted the white man’s way of life.”

The CRC commented: “There’s nothing wrong in showing the rural life of the people of these great continents, but this lifestyle is often used as a comparison to life in western society — no proper assessment is made of the values of living rurally and no positive picture of their communities emerges.”

Negative impressions were often reinforced by the use of words such as primitive, unsophisticated, underdeveloped, etc, and “titles as well as substance can affect the way in which a child views the contents of books”. One example was Strange People in Strange Lands by L R Hawkes (1963) where, the report noted, “all the strange people are black”.

Illustrations also tended to perpetuate stereotypes. Out of 124 illustrations in Living in Other Lands, the report said, only four showed black people “in positions of authority, or doing a job or profession requiring other than basic limited skills”.

Books discussing South Africa generally avoided mentioning apartheid (established in 1948) or skirted around it:

“In South Africa, where the white man’s safety and welfare must be safeguarded, it is not easy to give Africans equal rights and responsibility.” — The British Commonwealth and Empire, by M Masefield (revised edition, 1959)

Meanwhile, Our Commonwealth, by R W Purton (1958) talked about “racial segregation” — which “seems unfortunate” but its results “must be left for the future to tell.”

The report commented: “The people of South Africa are not seen as people, but as Europeans and Bantus … The European is portrayed as one who has a mission to help the African. His position is superior, he is cleverer, has foresight compared with his African counterpart. The African is portrayed in what might be described as a ‘sambo’ personality — helpless, lacking in foresight and therefore in need of guidance.”

Books of that kind, the report suggested, “fail to appreciate that when a group of people (in this case the indigenous population) are invaded by outsides who they see as posing a threat to their land, cattle and women, the logical step is one of defence.

In Baden-Powell, Chief Scout of the World, by Wyatt Blassingame (1966), Powell is described as a “hero of the British empire” who “had trouble with the natives” in South Africa.

Stories for children

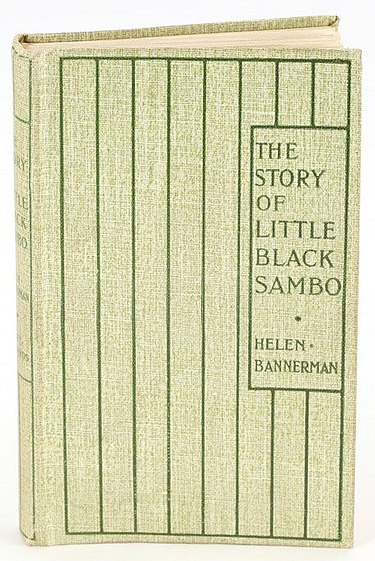

The report also took a brief look at some objectionable examples of fiction for children. It “unequivocally” condemned Enid Blyton’s tale of the three golliwogs along with The Story of Little Black Sambo written and illustrated by Helen Bannerman. Originally published in 1899, the latter could still be found in the multi-racial schools of Toxteth. The book’s title alone should preclude its use because the word ‘Sambo’ is derogatory, the report said. “We know of instances of black children being called ‘Black Sambo’ in an infant class where The Story of Little Black Sambo was read.”

Meanwhile, the Dr Dolittle stories, first published in 1920, “perpetuate every known prejudice against someone of another race,” the report said. One especially objectionable story “tells how the doctor tried to turn Prince Bumpo white, because he wants to return to the Sleeping Beauty who spurned him because he was black”.

A similar idea can be found in The Black Penny by Alan Drake (1959) where an old black penny is rejected by the “shiny and new” coins in a boy’s money-box. The boy polishes it up and the other coins then find it acceptable.

Sounder, by William Armstrong, is a novel for older children which won an award when first published in 1969. It’s the tragic story of a black share-cropping family in the southern United States — based on an account told to the author by a black teacher decades earlier.

The style of the story is so isolated and so completely void of feeling that it becomes obvious to the reader the author has never experienced what he is writing about,” the report said. “We see the family placed in conflict situations with acts of God rather than the society they are suppressed by.”

‘A sense of proportion’

Neither the Commons committee nor the Local Education Authority appears to have been alarmed by the CRC’s findings. The MPs commented in their report:

“The contents of school books were mentioned by several of our witnesses, the usual complaint being of racial bias, slighting references to other peoples and cultures and slanted versions of history. Such books exist but we think it wise to keep a sense of proportion.

“Some of our witnesses listed unsuitable works of fiction for the young. Even if they do contain racial innuendos we doubt whether many of them are recommended reading in schools. Education authorities cannot be held responsible for what is in the pubic libraries. It would be helpful to proffer positively good books rather than proscribe negatively bad ones.

“It has always been a weakness of some schools, for financial and other reasons, to use books which are out of date and/or badly written. It is regrettable, but it is nothing new.”

In Liverpool, meanwhile, the education authorities said schools were careful in their choice of story books for reading to children but “there appeared to be no reason to carefully scrutinise textbooks for racial bias. Anything which crudely intruded was rejected but few head teachers believed any positive search for bias was necessary.”

Their report added: “In any case the textbook is simply the tool and not the master of the teacher.” That, in effect, meant the onus was on teachers to deal appropriately with racist attitudes arising from books or from talk among the children.

However, evidence from the questionnaires showed most teachers were ill-prepared for the task. Many claimed to be colour-blind, saying they preferred to see “children as children, not as coloured or white” but, commendable as that might sound, it could easily become an excuse for ignoring difficult issues.

Teachers need to have the training and courage to deal with attitudes of pupils which arise within the school,” the CRC said. Some of them would call a halt to discussion when pupils started to raise racial issues because of the amount of emotion they generated. “Such situations are often outside the experience of the teacher.”

The education authority’s questionnaire asked schools: “What steps have you taken to ensure your staff are open minded and without prejudice?” Five county primary schools (out of 133) said they looked for any signs of prejudice at job interviews.

Many teachers plainly resented the suggestion that any action might be needed. One head teacher replied that it was “an impudent and stupid question.” Others, especially from church schools, claimed there was no risk of prejudice because the teachers were professionals and the school was run on Christian principles.

FURTHER READING

Commons Select Committee Report

This can be viewed at Liverpool Record Office together with the LEA and CRC submissions

Race and our schools

Discussion of the LEA and CRC reports

Liverpool Free Press, June/July 1973

Falkner Place – the causes still remain

Discussion of social tensions in Liverpool 8, by youth worker Chris Elphick.

Liverpool Free Press, Sept/Oct 1972

VIDEO: Liverpool 8

Jonathan Dimbleby investigates racial tension on Liverpool’s housing estates.

This Week, 1972

0 Comments