by SYLVIA HIKINS

There can’t be many (if any) cities in the United Kingdom where local poets have become household names, but in the 1970s and 1980s Liverpool was exactly that. The famous trio, Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten were the pinnacle of a large base of local poets whose emphasis was on performance. In the late 1960s, with support from the Merseyside Arts Association, a committee of volunteers set out to organise a springtime poetry festival. More than 300 poets registered to take part and the festival was unusual in that many of the events encouraged people in the audience to read aloud as well as listen. Running for more than fifteen consecutive years, the Liverpool Poetry Festival aimed to make poetry accessible to a broader audience.

This had important implications for the content of the festival and the locations where events were held. Much of English poetry was deeply connected to the world of academic elitism. Yet most of the earliest English poetry started off in the public arena, in the market square. If you go back to Saxon times, or before, you find it is essentially an expression of the people, most of it learned by word of mouth. The Liverpool festival reflected this, with readings taking place in pubs, clubs, parks, libraries, schools, community centres, tents, woodlands, churches, universities and on the streets. More than twenty poets performed readings for passers-by in Williamson Square.

Others placed a podium at the lower end of Bold Street where shoppers could stop and have a poem written especially for them to take home along with their shopping. The guidelines for the poets taking part were: “If you can’t think of anything immediately, write about the shoes they are wearing, where they might be walking to next.” This event, repeated over several years, was immensely popular. People queued up to get their own unique poem, demonstrating that the effect of verse is in many ways more significant than its structure – proof it has a place on the streets, in places where people communicate.

If you lived or worked in Liverpool, you couldn’t help observing what was actually happening, and commenting on it. The city was experiencing difficult times – the shutting down of the South Docks, factory closures, high unemployment, families forced to live their lives in poverty. Following the 1981 Toxteth riots several ministers in the Thatcher government privately advocated abandoning the city to “managed decline“.

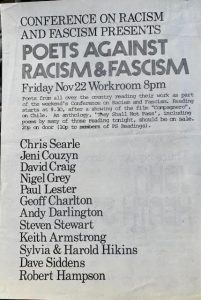

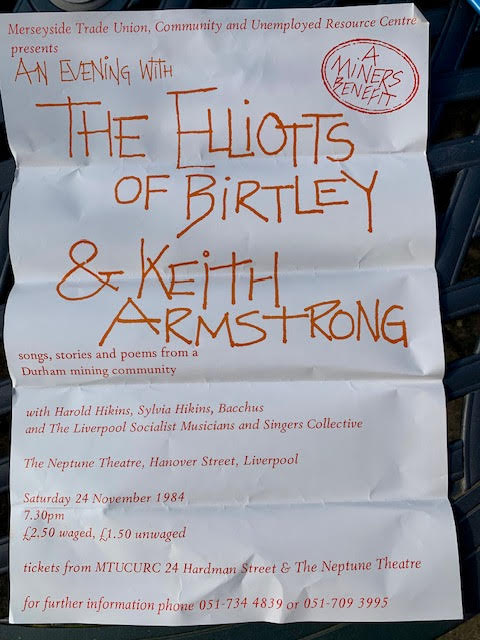

Communities continued to respond to the worsening conditions. Many Liverpool poets were involved in collectively organising and taking part in events. They supported Poets Against Racism and Fascism and raised money for the miners’ strike with a performance at the Everyman Theatre which included songs written and performed by Jake Thackray. There was also an evening of music and verse in response to the Everyman Theatre Access Appeal that, as well as local poets, included the dissident Russian poet, Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

In 1974, more than 150 people attended the Bluecoat Hall for an evening of poetry plus music from Quilupayan, a Chilean folk group exiled from their homeland after a political coup. All proceeds from this concert went directly to Chilean refugees living in Liverpool. Many Liverpool poets were also community activists. Ed George promoted community events with Bill Harpe at the newly-developed Blackie, formerly the Great George Street Congregational Church.

Dave Ward and Dave Calder founded the Windows Project that took its specially created games into local communities where people, in particular teenagers, were encouraged to use their imagination to discover their inner voice, so often silenced by other circumstances, and express this in writing.

Dorothy Kuya, the prominent Liverpool 8 activist, got special funding for an inner-city “Story Cart” which I took out for several summers during the school holidays. It was an old wooden builder’s cart pulled along by two young men, and we parked it alongside Princes Avenue Methodist Church, laid a tarpaulin on the ground, then encouraged local children to sit there and engage with poetry writing. Once written, the poems were immediately printed out on a Banda duplicating machine.

This was a hugely popular activity. One evening a young boy, holding a brush and paint, disappeared into the small community building behind the church where he painted in large letters on the dark wooden floor: “White and black / Black and white / Live together / Don’t fight”. He was a true people’s poet demonstrating how powerful even a short poem can be in conveying an important message.

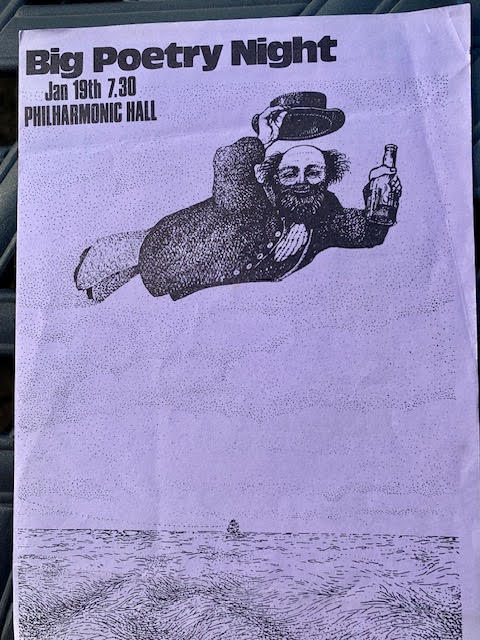

Liverpool poetry was not confined to pubs, clubs and the streets, though, In both 1972 and 1973, the poetry festival also included a Big Poetry Night at the Philharmonic Hall where a wide range of Merseyside poets from diverse backgrounds read to a packed audience of 1,700 people, about which The Liverpool Echo wrote: “It’s happening. It will make you both laugh and cry. It will make people realise that poets care.”

The Big Poetry Nights poets reading from the huge Philharmonic stage included Matt Simpson, Sidney Hoddes, Henry Graham, Mike Law, Ed George, Malcolm Barnes, Spencer Leigh, Nigel Walker, Richard Hill, Brian Wake, David Porter, Dave Calder, Harold Hikins, Sylvia Rice-Smith (Hikins), Adrian Henri and Roger McGough. In 1974, as part of the Poetry Festival, Henri, McGough and Patten did a reading together at St. George’s Hall Concert Room, for the first time since anyone could remember.

Part of the intention was to have some fun and as Adrian Henri recited “Love Is”, Brian Patten removed all his clothes behind the scenes then streaked across the stage. It both surprised Adrian and astonished the audience. You never knew what might happen at a Liverpool poetry event.

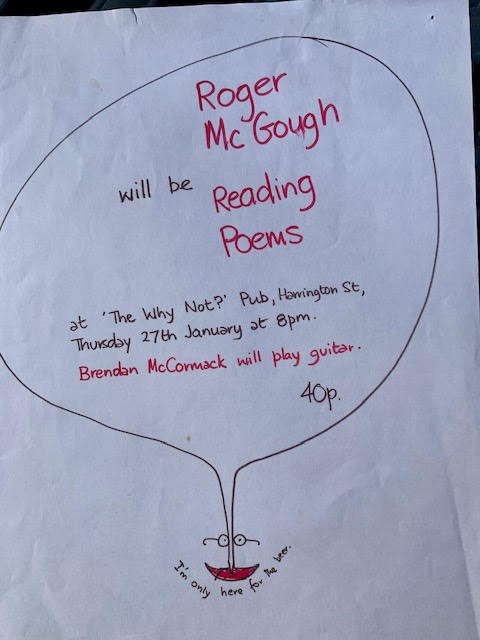

All through the 1970s and 1980s, alongside these formal poetry events, there were regular gatherings at Liverpool City Libraries, Sampson & Barlows (a popular restaurant on London Road), O’Connors, Jessie’s, the Everyman Bistro, the Why Not pub on Harrington Street, plus, across the Mersey on the Wirral, Jabberwocky monthly gatherings, often held in Burton Woods.

The Merseyside Arts Association played an important supporting role in this, “We’re fairly hard up,” it told the Daily Post & Echo in the early 1970s, “but we’ve allocated £2,300 in poetry promotion over the past two years. We have helped set up the Merseyside Poetry Circus. We have organised major monthly readings in Hope Street. We do not discriminate.”

Every month poets and audiences would join together in an informal atmosphere, usually over a glass of beer, listen to verse reflecting life in general, poverty, racial discrimination, equal rights, the conflicts in Vietnam and Northern Ireland. At the end of each session there was usually an open mic that invited people in the audience to participate. Music was an important part of the poetry scene too, since a song is, in essence, a poem set to music. The Poetry Circus, with its large register of Liverpool poets, in its visits to pubs, clubs, schools, universities, always combined the two – verse and music – usually in the form of folk music.

A Poetry Circus gathering at Crosby library

At Poetry Circus events, both poems and songs were sometimes written specifically for the local community. One was “Naptha Johnny”, a poem/song about the problems Dingle residents were experiencing from the naptha tanks at an oil depot nearby. Another – “Bring Back the Scousers” – focused on the re-housing of people miles away from the districts where they had spent most of their lives. Providing musical interludes was the talented Rusty, comprising Alan Mayes and Declan Macmanus, a popular duo who wrote their own songs. Macmanus later became famous as Elvis Costello and he mentions these poetry readings in his autobiography.

Poetry in Liverpool in the 1970s and 1980s, based on interaction, was popular and had a significant following. But running alongside this was strong opposition from some literary critics and academics based on the myth that, when it comes to literary standards, if poetry is popular, it can’t be any good. In response to criticism from sections of the mainstream, who so often viewed poetry as a precious art reserved for an educated elite, Adrian Henri wrote: “Some people seem to believe that if it’s popular it can’t be poetry. What I find very irritating is that these people think you think like they think.” (i.e that there’s only one way to write a poem).

In reality, the poetry scene reflected Liverpool, a city brimming with talent at all levels. If you don’t have much disposable income you make your own entertainment, create a social background that is populist, not elitist. While the emphasis in Liverpool was on the spoken word, there was still a major demand for books. “The Liverpool Scene”, Edward Lucie-Smith’s anthology of work by Henri, McGough and Patten, sold more than half a million copies.

Lesser-known poets struggled to find a publisher because of lack of funding grants, which is why, in 1972, I founded Toulouse Press (so-called because the terraced house in Dingle where I lived had two loos – one in the yard, one upstairs). In 1979, Gladys Mary Coles also established Headland Press and we both concentrated on publishing a wide range of Merseyside poets. All profits were re-invested to achieve further publications of both solo collections and monthly magazines such as PM (Poetry Merseyside).

The poetry book funded by USDAW

In 1973 Liverpool Trades Council celebrated its 125th anniversary and to mark this occasion it asked Toulouse Press to edit and publish two hardback books: “Building the Union”, a history of trade unions in Liverpool, and “Roll the Union On”, an anthology of poetry funded by the shopworkers’ union, USDAW. With the work of 44 Merseyside poets past and present, it included rhymes collected from children as they played games in their school yard on Scotland Road – verses no doubt picked up by word of mouth from their parents, like this one:

Mary Ellen at the pawn-shop door, A bundle on her head and a bundle on the floor, She asked for seven and six But he only gave her four, So she knocked the bloody knocker Off the pawn- shop door.

This was a time when there were many independent bookshops in Liverpool that would happily sell and promote small press publications. But now, 50 years on, only News from Nowhere, organised as a collective, has survived. However, a book only becomes alive when it is taken off the shelf and read. Liverpool’s hugely popular poetry following was based on the spoken word, modern, thought-provoking entertainment, often crammed with Scouse wit. It reached out to ordinary people, exploited its enormous potential to connect with us all, plus interlinking with other forms of expression – music, story-telling, social and political issues.

In Liverpool during the 1970s and 1980s, poetry was the stuff of life, often as ragged and untidy as life itself. Nothing to do with ivory towers. On all fronts, the city never promoted seclusion or separation from the facts and practicalities of the real world. Poetry came from, and belonged to everyone. A true Liverpool tradition.

Sylvia Hikins is an English poet, publisher, painter, and broadcaster. Together with her late husband, Harold Hikins, she ran Toulouse Press, and collaborated on various poetry and avant-garde art works.

* * *

A selection of poems

The poems below are from a special edition of Arts Alive Merseyside that focused on the Big Poetry Night

0 Comments