Old Swan was a rather drab and ordinary part of Liverpool that traffic whizzed through with no particular reason to stop. For a few days in 1976, though, it became an extraordinary place where residents held a community festival described as “an explosion of colour and noise”.

It began with a grand parade and ended with the re-enactment of a civil war battle between Cavaliers and Roundheads. In between, there were performances by street entertainers, football matches (for women as well as men) and dozens of street parties plus general merrymaking.

In the midst of that it wasn’t always clear where reality ended and the entertainment began — which in a way added to the fun. Residents of one street complained about “vagabonds and gypsies” hanging around their party and asked the organisers to get rid of them. The apparent vagabonds were actually from a London-based theatre group, Action Space, and the organisers replied: “We’ve paid £400 for them so you’ll jolly well enjoy them.”

Meanwhile, a group from Leeds called the John Bull Puncture Repair Outfit pretended to be making a film about Mexican bandits — with cine equipment made from cardboard and other bits and pieces. Such was the excitement this caused that the man posing as the star of the film later spent 20 minutes signing autographs.

The fake film crew in action

At the same time, though, someone else was actually filming the festival — including the melee around the fake crew. This was David Clapham who had begun experimenting with cine after someone donated a camera to the art college where he lectured. “A lot of the stuff I was doing was very arty,” he recalled – “conceptual art type things” – but he later began making short documentaries.

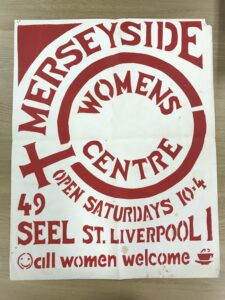

Word of this reached Colin Wilkinson from the newly-established Merseyside Visual Communications Unit (MVCU) which had a mission to “make more people aware of the many positive ways in which film, photography, video and sound recording can be used in a social, cultural and educative context”. Initially based in Seel Street and later in a former pub on Whitechapel, it eventually developed into the Open Eye Gallery.

“Colin came to see me and asked if I would like to join,” Clapham said. “It was good because there were only about four of us. It was a nice, compact little unit.” As a bonus, this also gave him access to a more plentiful supply of film.

Nowadays, almost anyone can make a video of themselves and friends, and post it on the internet where anyone can see it. In the 1970s, though, creating moving images was mostly an elite activity, confined to cinemas and television. The barriers to using film in a community setting were technological and financial: the equipment was bulky, complicated and expensive — not to mention the film itself.

Clapham was using 400-ft reels of 16mm film — the standard for TV — which had a running time of only 12 minutes. There was nowhere in Liverpool where the film could be developed, so it had to be sent off to London. Once it had been developed there was then the laborious task of editing: physically cutting and splicing sections of film. The cost of 12 minutes of film, including developing, was around £400 (several thousand in today’s money).

In 1974, under MVCU auspices, Clapham made a short documentary of the Granby festival in Toxteth — which he believes was the first ‘community film’ made outside London.

“It was a deliberately rough hand-made looking film because I thought that reflected the kind of community thing,” he said — and it seemed to go down well. The Arts Council loved it and it was distributed by the British Film Institute. We sold it on to Swedish television — a guy turned up and said they were very interested in these concepts in Sweden.”

He continued: “After that we were encouraged to do another one and we did a recce. I had gone round and taken photographs of all the streets in Old Swan, talked to people in the area and realised they were up for it. I approached them asking if they would like to be part of a community festival in the area. The add-on bit was that the unit would be given the money to film.”

A 25-minute version of the film, titled Super Swan, has been preserved by the North West Film Archive at Manchester Metropolitan University and can be viewed on Vimeo. There are several shorter clips on Youtube, including this one.

For residents in Old Swan, this was the first time they had seen a movie camera focus on them and how they lived, Clapham said. “It was good because they started to see themselves in action. Then they got quite intrigued by how they looked. Loads of people used to turn up to screenings when we had made the film. We did a number of screenings in Old Swan and they were packed.”

He added: “I found that quite rewarding but it wasn’t sustainable because of the expense.”

Change was on the way, though, as video recording began to take over from film. There were parallels here with earlier technological developments that had made printing and typesetting cheaper and more accessible — and led to a burgeoning of community newspapers in the 1970s.

MVCU had begun using black-and-white video equipment in the 1970s which was cheaper and simpler to operate than cine. Video removed the need for expensive film and the wait while it was developed. It also took away the need for projectors and darkened rooms in order to see the results: recordings could be played back instantly by plugging into an ordinary TV set.

“We didn’t have anything sophisticated in terms of editing but we had a basic kit,” Clapham said. “We used to hire it out, and it was out all the time. People came from different groups and used it for their own events. They preferred to hire the stuff from us and film their own things in their own way than have a crew to do it our way.”

Video cameras were still bulky, though, and sometimes had to be perched on the operator’s shoulder. Technological improvements continued and by the 1990s they had shrunk to a more manageable size. Mass production reduced the price to a few hundred pounds and they became a consumer product sold in high street shops rather than a specialist item.

0 Comments