In the early 1970s the police in Liverpool made extensive use of their powers to stop people in the street and search them. Writing about this years later, Ian MacDonald, a former assistant chief constable, described it as a key tactic in combating inner city crime.

Typically, the police would be looking for people carrying drugs, weapons, stolen goods or “implements”. The implements were usually filed-down car keys or single scissor blades which at the time were capable of opening and starting most cars.

Stop searches did detect and prevent crimes but they also had another effect. Only about 10% of searches resulted in an arrest while the other 90% tended to cause resentment among people who had done nothing wrong.

Worse, still, “rumours of officers fabricating evidence were prevalent amongst both the community and the Force,” MacDonald wrote. “Officers claimed that they knew of it happening to suspected offenders and residents claimed that they knew of it happening to innocent victims. They were probably talking about the same people.”

MacDonald’s article leaves no doubt that fabrication — such as officers slipping an “implement” into someone’s pocket during a search — did happen. It’s unclear how often this happened but the planting of drugs had become prevalent enough to be known in the Force as “agriculture”.

Two men acquitted

There were two notable court cases where a black man accused of possessing cannabis was acquitted after claiming police had planted it.

The first man, Lennie Cruickshank, had been arrested on Upper Parliament Street while making his way home from a night out and carrying his guitar. Police stopped him — initially on the pretext of suspecting the guitar had been stolen.

Cruickshank’s trial in Liverpool Crown Court lasted seven days and hinged mainly on the credibility of the police version of events. Cruickshank gave a statement [appended below] about his arrest and subsequent events in the Cheapside police station which described some appallingly unprofessional conduct by officers, as well as the liberal use foul language. In the end the jury believed Cruickshank’s version.

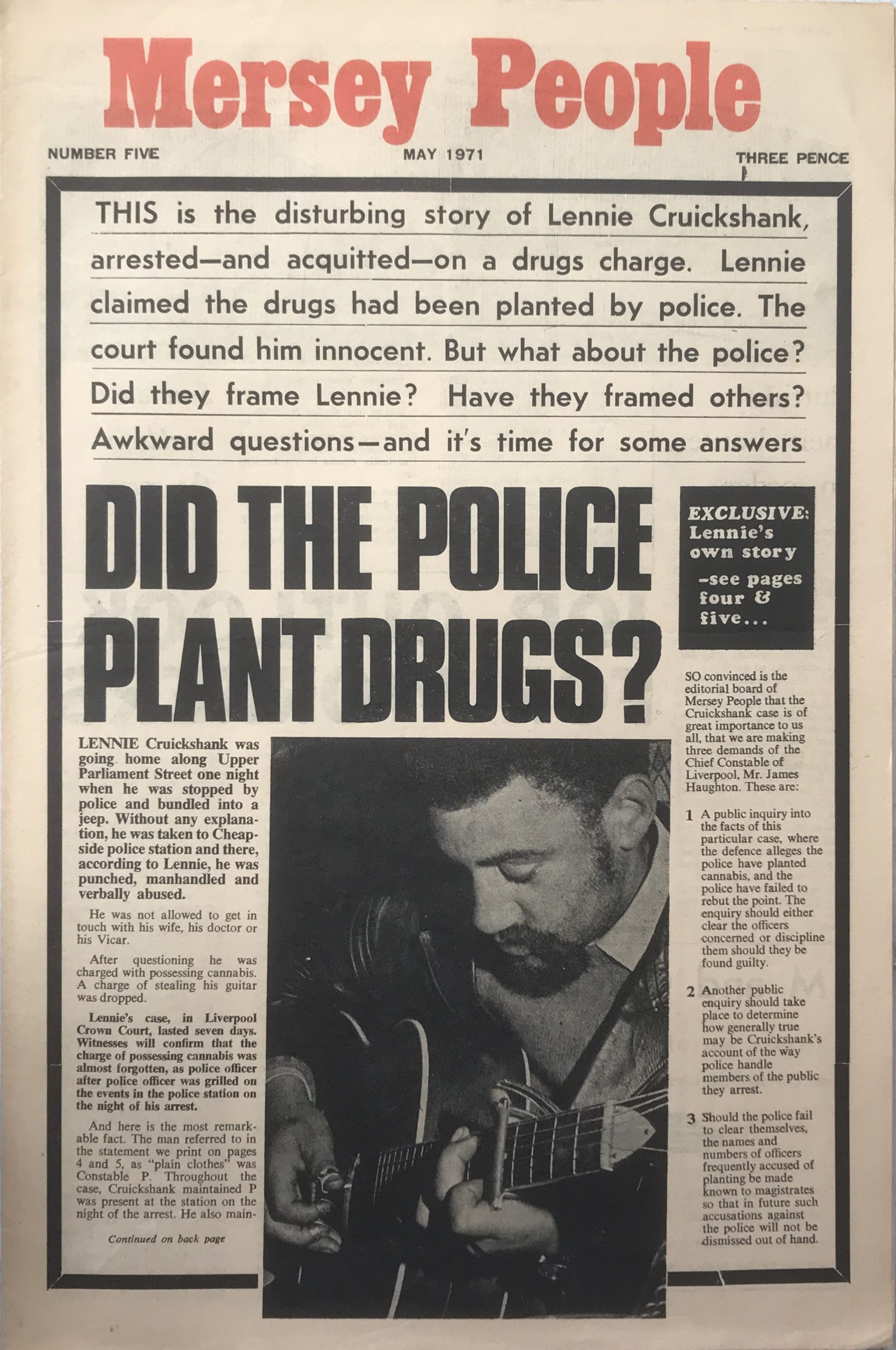

Cruickshank’s case was reported by the Mersey People.

‘Come here, sonny’

The second man, Jimmy Rogers, was walking down Sandon Street with his wife and some friends when a man in civilian clothes came up to him, clapped a hand on his shoulder and said: ‘Come here, sonny.’

Rogers told the Liverpool Free Press:

I turned round and said: ‘Who are you talking to?’ He said he was a police officer. I asked to see his identification. He whipped out a card and flashed it and put it back in to his pocket before I could see it properly.

Then a uniformed officer came up and pointed to his hat with his stick and said: ‘Isn’t this enough evidence?’

I told him I hadn’t committed any offence and said I was on my way home. As I turned to go he grabbed me and said: ‘Oh are you? Funny guy.’

He said he wanted to search me and I let him. He pulled out some letters from inside my jacket pocket, and a comb. Then he put his hand back in and said ‘What’s this?’ As far as I could see it was a small piece of silver paper. He started to open it and sniff it.

Sheila, my wife, said to him: ‘You’ve just planted that.’ The police officer then told me he was arresting me because he believed it was cannabis.

There was something the officer didn’t know at the time of the arrest, though, and only found out later: Rogers had spent two years coaching the police basketball team — reputedly the best on Merseyside — and the team’s manager, Superintendent Bob Alker, appeared in court as a character witness during the ensuing trial.

Astonishingly, on the evening after his acquittal Rogers was stopped by the police again. He was on his way to the YMCA gym where he coached a youth team. A police jeep pulled up and four officers jumped out. “Come here,” one of them shouted. “What’s in that bag?”

There was another incident one evening in October 1973. After a basketball game at the YMCA Rogers had stopped off for a meal at the kebab house in Hardman Street with Paul Ambrosius, a 20-year-old mixed-race player. Shortly after 11pm they passed the Hope Street police headquarters. Its door was open and they heard a uniformed officer say in a loud voice: “That’s all you can expect from niggers.”

Both men went into the station to challenge the officer — a sergeant — about his language. According to Rogers’ court statement there were also two civilians — potential witnesses — in the station at the time:

Paul asked one of the civilians if he had heard what the sergeant said. The civilian stiffened and said something to the effect ‘I have only just come in’.

The sergeant said to the civilian: ‘No … you didn’t hear anything, did you?’ The civilian did not reply.

We waited until the civilians had finished their enquiry and then I asked the sergeant why he had used such a derogatory term.

The sergeant responded by accusing Rogers of using foul language, which Rogers emphatically denied. Two other officers made a feeble attempt to support the sergeant by claiming they had seen Rogers in the street with a group of teenagers a few minutes earlier, “messing about” with cars.

At the time of the incident Rogers was working for the recently-formed Community Relations Council and when the officers found out they backed off and started addressing him as “Mr Rogers”. They then switched their attention to Ambrosius who, despite his denials, was charged with using obscene language and eventually fined £5.

Jimmy Rogers (far right) and his team. Paul Ambrosius is player No33.

Rogers had never met his parents. He grew up in an orphanage as the only black child. At 15 he joined the army and was posted to Germany where he became a physical training instructor. After leaving the army he settled in Liverpool, got a job in the Ford car factory and played competitive basketball in his spare time.

In 1968 he was selected to play for Great Britain and in Liverpool the police sought to recruit him for their team — which would have meant also joining the force. He balked at becoming a police officer but agreed to coach the team.

In the early 1980s Rogers moved to London where in 1984 he founded the highly successful Brixton Topcats. He became seen as “a unique figure in the UK’s black self-help movement” and on his death in 2018 at the age of 78 London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, hailed him as an inspirational figure: “Through his passion for the sport, he changed the lives of countless young people.”

Further reading:

‘We could be anything we wanted to be’: remembering Jimmy Rogers

Michael Romyn, Race & Class, vol 61, issue 2, August 2019Jimmy Rogers, Brixton Topcats Founding Father Passes Away

Sam Neter, Hoopsfix, October 4, 2018Farewell to father of British basketball who discovered Luol Deng

Tin Lewis, The Guardian, October 6, 2018

Drugs in desk drawers

Both Rogers and Cruickshank lodged complaints about their arrests and, a year or so later, received letters saying no further action would be taken. There were a few signs, though, that the Force was trying to crack down on “agriculture”.

The Free Press reported that desks and drawers used by members of the Vice Squad were being regularly searched by other officers. The paper quoted a member of the Vice Squad as saying they had previously been allowed to keep drug samples.

“Just by comparing drugs which we seized, with our samples, we knew exactly what kind they were … long before the analyst gave us his report,” one officer told the paper. “But since all this fuss, our desks have been searched frequently and completely out of the blue. Now, we’re not supposed to keep any drugs, though of course some still do.”

There were rules for carrying out stop searches and the reasons for them were supposed to be recorded (though they often weren’t). It wasn’t enough to stop someone simply because they looked dodgy. On the other hand, it was OK to stop them if two officers said they had seen the suspect trying car door handles twice.

“Conducting stop checks was and always will be a very tricky business.” MacDonald wrote in his article. “If the person being searched has nothing on them then they and their families and friends and passers by are likely to be affronted, outraged, aggressive, even violent” — though he noted that this could also be the outcome if the person had been doing something illegal.

According to MacDonald the problem was partly a result of inadequate training and supervision, though some officers also lacked the aptitude for carrying out stop checks “in a positive, tranquil and effective manner”.

Inevitably, this had an effect on police/community relations and became a contributing factor in the 1981 Toxteth riots. At one point the chief constable became so concerned that he banned the notorious Operational Support Division from operating in that area.

MacDonald comments: “It took more than this to stop them.” Operational Support hung around the Toxteth borders and would sneak in to make arrests. Much to the surprise of the prisoners they would tell custody sergeants and local magistrates the arrests had taken place somewhere else.

Further reading:

Police Power and Black People

Derek Humphry and Gus John. Panther Books, 1972Before the Windrush: race relations in twentieth-century Liverpool

John Belchem. Liverpool University Press, 2014

Lennie Cruickshank’s testimony

This is the statement made by Lennie Cruickshank in his defence against a charge of cannabis possession (originally published in the Mersey People). It reveals much about how police in Liverpool operated at the time.

After going out on Tuesday evening I was returning home on foot and reached the junction of Upper Parliament Street and Berkeley Street at approximately 12.45 a.m. My intention was to engage the free taxi that was at the rank. I stopped at the kerb, because there was a vehicle approaching. It turned out to be a police jeep, and stopped at the lights. After checking to see that the road was clear, I was about to cross when the rear door opened and I think five officers got out. There was one sergeant and four constables.

The sergeant said, “Where are you going?”

I replied, “I’m going home.

The sergeant said, “Where’s home?”

I pointed to Princes Avenue and said, “Just along the road there.”

He then mimicked, “Just along the road, eh. A wise guy, eh?”.

I answered the sergeant. “No, I’m not a wise guy, but that is where I was going.”

He then asked me: “What’s your name?”

I asked him, “Would you please tell me why you’ve pulled me up and are asking me all these questions? And I don’t see why I have to go through all this.”

One of the other officers said: “What have you got in your pockets?”

Another one said, “Who do you think you are, anyway?”

One of the officers then went to the jeep and opened the rear door, and said: “Well, come on then, let’s go.”

Me: “What for? Are you arresting me?”

The other officer said, “Never mind that, get in.”

Me: “What are you charging me with?”

Another officer: “We’ll worry about that when we get down there. Don’t worry, we’ll think of something.”

He took my guitar off me and gave me another push, and said: “Get in the back.”

When we reached the police station, they got out and one banged me on the head with my guitar and said: “Come on, f off out!”

Then, just before we went in, he said: “Get your hands out of your pockets. You’re our prisoner now, and you know what your rights are don’t you? Absolutely f___ ing nil!”

I was then pushed all the way along the corridor, passing another officer in plainclothes, who made a remark about having got another one. In the room I was told to sit down, and was pushed towards a chair. I was then asked my name and address. I asked: “What do you want to know for?”

The reply was: “So we can charge you.”

Me: “What with?”

“We’ll make something up.”

I was told to empty my pockets out, and I refused. Then I was told to take my coat off, and again I refused. They then took it off me by force, and my trouser pockets were emptied by the police. They also emptied my jacket pockets and threw it on the floor. They then took all my possessions over to a table.

The plainclothes man who we passed in the corridor then came in and went up to the others at the table, and looked at my property. He then said: “I’ll show you how to make the black c ___ talk,” and dragged and hit me in the face and ribs. I was knocked to the floor. I was then dragged up and was pushed towards the chair and told to sit down. I was about to but was knocked onto the floor.

I was then asked if I worked, and one officer said, “That bastard, he’s never worked in his life. I’ll bet he’s a frigging dole-ite!”

The other one said, “We need your address for the charge sheet, otherwise you’ll go to court as of no fixed address, and that would look nice for the magistrate in the morning, won’t it? You’ll be going to Risley in the morning by the way.”

At this point I looked at the sergeant and asked him, “Is all this necessary?”

They appeared to put my things back into the pouches. I noticed the sergeant and another officer plus the plain-clothes man put some paper (which, at the time, I took to be one of my payslips, into the suede pouch and push it well down.) He then turned and said “f___ing half-caste bastard,” and walked out.

One of the other officers said “Where do you live?”

Me: “Why?”

Him: “For the charge sheet.”

Me: “On what charge?”

Sergeant: “How will cannabis do?”

Me:” I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

I was still on the floor when one of the others came towards me, and I thought he was going to hit me with a chair he had picked up so I said to him: “Hang on, before you go any further I’ve had rheumatic fever and I’ve got a bad heart.”

Him: “A likely f___ing story. I’ve heard that one before. Look at him, he should get an Oscar for good acting.”

At this point three CID men came into the room and asked what was going on. One officer said: “He doesn’t want to talk.”

I was dragged off the floor and told to go with them. In the CID room I was told to sit down and asked what the trouble was. I told him the entire incident and complained that I still did not know why, or if, I was charged with anything. He asked me why I thought I had’ been brought in.

I told him that, as far as I could see, there was no reason. Unless it was because I wouldn’t tell them my name and address. One of the others then said: “I suppose you’ll be telling us you’re only getting picked on because you’re coloured next.”

Me: “You brought that up, not me. I’ve no reason to say it. Mind you, now that you’ve mentioned it, a fellow in there made reference to it.”

First CID: “We’re not treating you like that, are we?”

Me: “No, but it’s a bit late now, I’ve already been beaten up.”

Him: “I can only do the best I can. I’m here to help you. What’s your complaint?”

Me: “The very fact that I’m here now without reason. It’s no use you being nice now, is it? I’ve already had the maltreatment.”

When we went back in, they asked him what he had found out. His reply was “Nothing, I’ve found out as much as you have.” He then went out.

They then picked all my things up and said: “Here, get hold of these.”

I said: “No, you can keep them.” I was then told to pick my coat up. I refused. It was thrown at me, and I was pushed out of the room.

I was taken to the charge desk by a constable, who said to the inspector: “I was walking along the road, sir, and saw him approach another man and get this paper parcel off him, and put it in his pocket. I went over to him and cautioned him. I arrested him at 2 a.m., and when I searched him I found this.” He showed him my suede bag, and opened it and took out some paper. “It’s cannabis. Well, I think it is. I’m not sure.” The inspector said: “Oh yes, that’s cannabis alright. In fact, it’s resin.”

He also charged me with stealing my guitar. These two charges were written out on a charge sheet.

The inspector said: “I won’t accept this one about the guitar” and crossed it off. I asked him why he was not accepting the guitar charge. He said: “Look here, all he does is come in here and comes before a senior officer and lays his charge; then it is up to the senior officer, which in this case happens to be me, whether to accept the charge or not. And I don’t wish to accept the guitar charge. But I will accept the cannabis charge. It is cannabis, isn’t it?”

Me: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen cannabis in my life. I don’t know what it looks like.”

Him: “Are you sure you don’t smoke cannabis? Your eyes are very bloodshot, how come?”

Me: “The reason why my eyes are bloodshot is because I’ve just been punched in them by one of your colleagues, which I don’t suppose you would be prepared to believe.

Him: “If you’ve got any com-plaints to make, you can go along to any police station in the morning and make them there. Have you been drinking tonight?”

Me: “Yes, I’ve had a couple of pints.”

Him: “I thought so, drunk as well.”

Me: “Far from it. As a matter of fact, I would like to see the police doctor and blow up a breathaliser, and be tested for this drug business.”

One of the others said: “Well, you’ve just missed him, he went home about ten minutes ago.”

Me: “In that case, I would like to see my own doctor, because I don’t feel too good after being knocked around.”

The inspector said: “It’s too late to be getting him out now.”

Me: “In that case, I would like to get in contact with somebody else.”

Him: “What for?”

Me: “Because I thought that I was entitled to get in contact with somebody, if I’ve been arrested.”

Him: “Who do you want?”

Me: “I’d like to contact Godd-ard, he’s the Vicar.”

Him: “No, it’s too late. I don’t think he would be very pleased getting disturbed at this time.”

Me: “On the contrary, he would only be too pleased to come down at once.”

Me: “Will you please inform my wife, and ask her to come down and bail me out.”

This was ignored, and I was taken away and locked up.” The following morning, before going into court, I asked if I could make a phone call, as I had not seen my wife.

The officer said: “No! What the f — ing hell do you want? You could be phoning anybody up”’

urther I’ve had rheumatic fever and I’ve got a bad heart.”

Him: “A likely f___ing story. I’ve heard that one before. Look at him, he should get an Oscar for good acting.”

At this point three CID men came into the room and asked what was going on. One officer said: “He doesn’t want to talk.”

I was dragged off the floor and told to go with them. In the CID room I was told to sit down and asked what the trouble was. I told him the entire incident and complained that I still did not know why, or if, I was charged with anything. He asked me why I thought I had’ been brought in.

I told him that, as far as I could see, there was no reason. Unless it was because I wouldn’t tell them my name and address. One of the others then said: “I suppose you’ll be telling us you’re only getting picked on because you’re coloured next.”

Me: “You brought that up, not me. I’ve no reason to say it. Mind you, now that you’ve mentioned it, a fellow in there made reference to it.”

First CID: “We’re not treating you like that, are we?”

Me: “No, but it’s a bit late now, I’ve already been beaten up.”

Him: “I can only do the best I can. I’m here to help you. What’s your complaint?”

Me: “The very fact that I’m here now without reason. It’s no use you being nice now, is it? I’ve already had the maltreatment.”

When we went back in, they asked him what he had found out. His reply was “Nothing, I’ve found out as much as you have.” He then went out.

They then picked all my things up and said: “Here, get hold of these.”

I said: “No, you can keep them.” I was then told to pick my coat up. I refused. It was thrown at me, and I was pushed out of the room.

I was taken to the charge desk by a constable, who said to the inspector: “I was walking along the road, sir, and saw him approach another man and get this paper parcel off him, and put it in his pocket. I went over to him and cautioned him. I arrested him at 2 a.m., and when I searched him I found this.” He showed him my suede bag, and opened it and took out some paper. “It’s cannabis. Well, I think it is. I’m not sure.” The inspector said: “Oh yes, that’s cannabis alright. In fact, it’s resin.”

He also charged me with stealing my guitar. These two charges were written out on a charge sheet.

The inspector said: “I won’t accept this one about the guitar” and crossed it off. I asked him why he was not accepting the guitar charge. He said: “Look here, all he does is come in here and comes before a senior officer and lays his charge; then it is up to the senior officer, which in this case happens to be me, whether to accept the charge or not. And I don’t wish to accept the guitar charge. But I will accept the cannabis charge. It is cannabis, isn’t it?”

Me: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen cannabis in my life. I don’t know what it looks like.”

Him: “Are you sure you don’t smoke cannabis? Your eyes are very bloodshot, how come?”

Me: “The reason why my eyes are bloodshot is because I’ve just been punched in them by one of your colleagues, which I don’t suppose you would be prepared to believe.

Him: “If you’ve got any com-plaints to make, you can go along to any police station in the morning and make them there. Have you been drinking tonight?”

Me: “Yes, I’ve had a couple of pints.”

Him: “I thought so, drunk as well.”

Me: “Far from it. As a matter of fact, I would like to see the police doctor and blow up a breathaliser, and be tested for this drug business.”

One of the others said: “Well, you’ve just missed him, he went home about ten minutes ago.”

Me: “In that case, I would like to see my own doctor, because I don’t feel too good after being knocked around.”

The inspector said: “It’s too late to be getting him out now.”

Me: “In that case, I would like to get in contact with somebody else.”

Him: “What for?”

Me: “Because I thought that I was entitled to get in contact with somebody, if I’ve been arrested.”

Him: “Who do you want?”

Me: “I’d like to contact Goddard, he’s the Vicar.”

Him: “No, it’s too late. I don’t think he would be very pleased getting disturbed at this time.”

Me: “On the contrary, he would only be too pleased to come down at once.”

Me: “Will you please inform my wife, and ask her to come down and bail me out.”

This was ignored, and I was taken away and locked up.” The following morning, before going into court, I asked if I could make a phone call, as I had not seen my wife.

The officer said: “No! What the f — ing hell do you want? You could be phoning anybody up.”

0 Comments