The Fisher Bendix factory in Kirkby had been built with government help to ease unemployment in the area. It wasn’t a success and in 1972 when the owners tried to shut it down workers occupied the factory in an effort to save their jobs. Three years later they began running it themselves.

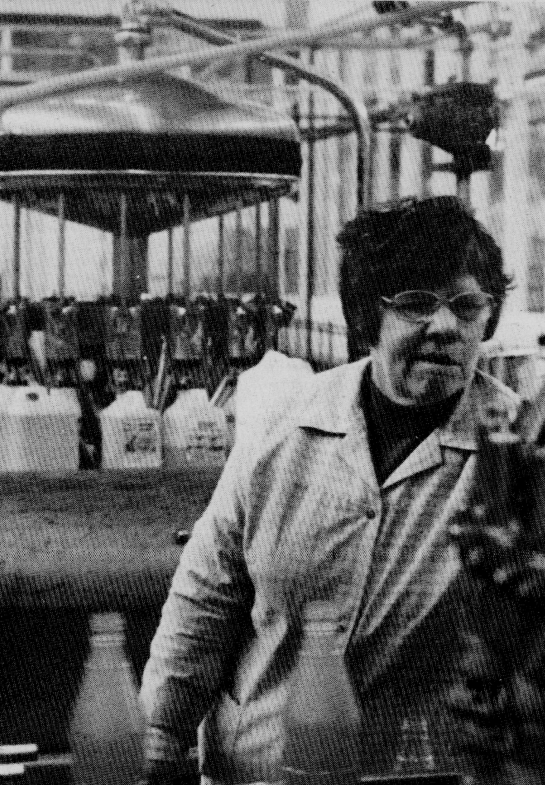

The entrance to the Fisher Bendix factory

In 1960 bulldozers moved into fields on the outskirts of Kirkby to begin construction of a new industrial estate. It was part of a government scheme to bring jobs to areas of high unemployment and there were hopes that the first factory to be completed — known throughout most of its existence as the Fisher Bendix factory — would provide work for more than 1,500 people making washing machines, dryers, and refrigerators.

The Board of Trade provided money up front, paying the £3.25 million construction cost. It then sold the completed factory (on favourable repayment terms) to its operator, the Fisher Ludlow company, a subsidiary of the British Motor Corporation.

Despite that initial help, the Fisher Bendix factory was unprofitable for most of its existence. It struggled under a succession of different owners and frequent management changes. By January 1972 its workforce had dwindled to 600 when Thorn Electrical, the latest owner, announced the factory’s closure.

With little prospect of finding alternative jobs, the workers refused to be sacked. They occupied the factory and posted the words “UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT” in capital letters three feet tall on the perimeter fence.

It was a startling development. Though occupying factories was not unusual as a form of protest in other parts of Europe, it was the first time in living memory that such a thing had happened on Merseyside. There were sometimes brief sit-down strikes inside the workplace but this was an open-ended round-the-clock occupation with the managers locked out, and it had plenty of public support.

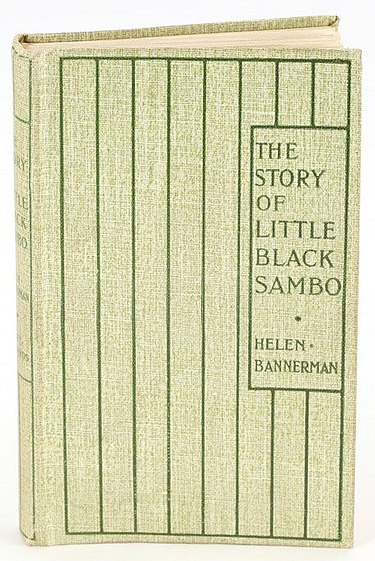

Note: A detailed account of the occupation and the events that led to it can be found in “Under New Management?” — a pamphlet by the political group Solidarity. Big Flame, a newly emerging political group at the time, issued a leaflet giving an account of how workers had entered the boardroom and ordered management to leave. Big Flame also took issue with Solidarity’s pamphlet and circulated a letter accusing Solidarity of being “divorced from working class struggles”.

Making money behind the scenes

As the workers struggled to save their jobs, though, others were making money behind the scenes — in particular a Swiss-based financier named Ivor Gershfield who ended up a million pounds richer.

A few months earlier Thorn had agreed to sell the factory building though the workers weren’t informed until four days after their occupation began. The sale was the first step in the company’s plan to close the factory and transfer its equipment to places where labour was cheaper.

Thorn sold the factory to Stanbourne Properties, a company owned by Gershfield which paid £1.2m. Gershfield’s company promptly re-sold it for £1.8m and a complex series of transactions involving shares and companies registered in tax havens brought his total profit to £1m or more.

The outcome of all this financial conjuring was that International Property Development (IPD), a public company with interests in Britain and Trinidad, emerged as the factory’s new owner and, fortunately for the workforce, planned to keep it running. IPD took over some of the engineering work previously done under Thorn and one of IPD’s subsidiaries, a soft drinks bottling firm, also moved in. For a while it seemed that the factory been saved but just two years later the money ran out and a receiver was called in.

The workers take charge

The receiver concluded there was little hope of finding another firm to take over the running of the factory. Short of closure, the only option left was for the workers to run it themselves as a cooperative — and they sought help from Tony Benn, the Labour government’s secretary of state for industry.

In November 1974, despite warnings from the Industrial Development Advisory Board that the factory could not become viable, the government agreed to provide a £3.9m loan.

For legal purposes a limited company called Kirkby Manufacturing and Engineering (KME) was formed and two union officials — Jack Spriggs, the T&G convenor, and Dick Jenkins, the AUEW senior steward — were elected as directors. Workers who had been employed for more than a year were allowed a £1 share and there were to be no external shareholders.

There was also an elected workers’ council consisting of a representative from each of the six unions in the factory, plus a management representative.

Financial burdens

KME was probably doomed from the beginning, and the surprising part is that it survived until 1979. The unions and their advisers had originally asked the government for £6.5m but had to settle for £3.9m. A huge part of that — £1.8m — was paid to the receiver for plant and machinery and a further £100,000 went as an advance for leasing the factory.

After these deductions KME was left with just £2m as working capital.KME was also paying over the odds to rent the factory, since it needed only about 60% of the building. An intensive search for different products to make in the unused space did result in two new production lines — one for ventilators and another for hydraulic lifting equipment — but it was not enough.

Furthermore, the factory’s previous history made two of its main suppliers wary of doing business with KME. British Steel, which was owed £400,000 when IPD went bust, refused credit to KME for the first year or so. Rockware, whose glass was used for the soft drinks bottling operation, charged KME a 5% premium above normal prices in an effort to claw back some of the debt left by IPD.

Life in a cooperative

At the time there was a good deal of interest in “alternative” ways of living and working. The basic idea was that if people just sat back and waited for a revolution or the collapse of capitalism to bring about change they would probably be waiting for ever. Instead, they should initiate change at ground level by creating their desired future in the present.

This led to numerous experiments in working cooperatively, without bosses, but most of them were small-scale. Running the Fisher Bendix factory, with hundreds of employees, was a different matter and, in the words of Jack Spriggs, the cooperative element was “almost incidental”.

Fifteen months after KME was set up, the Free Press visited the factory to talk to the workers. “There’s not a great deal of difference,” one of them told the paper. “You still get here at a quarter to eight in the morning and go home at half past four.” They were not working “for the love of the cooperative”, he added. “We work to get money for our wives and families.”

But there were some changes. “Us and them” attitudes between unions and managers persisted to some extent but became more constructive. “Where we would [previously] jump in at the deep end as shop stewards, and probably defend the undefendable, we now have to sit down and look on its merits,” deputy convenor Stan Ely said. “Now there’s no conventional management pattern. There’s no one to kick, there’s no one to fight. The be-all and end-all is the good of the majority of people in the factory.”

One result of this was that the unions agreed to working arrangements which, at the time, were unusually flexible. The Free Press reported:

“There is now complete mobility of labour, and the members have to be prepared to work outside their skills. Someone who usually bottles orange juice could find themselves in the dispatch and packing room during cold spells when there isn’t much demand for orange juice. This naturally challenges many trade union attitudes.

“Once the factory was one of the highest paid in the area. Today the workers are among the lowest paid — a semi-skilled person getting a basic £43 a week … These developments are perhaps inevitable in a co-op starved of cash and struggling to survive …

“At the moment co-op members seem to be working harder, for lower wages, and with little more control over their working lives. It remains to be seen whether they will continue to be happy with this in the future.”

Fixing a leak in a radiator

Bottling soft drinks was one of the factory’s side lines

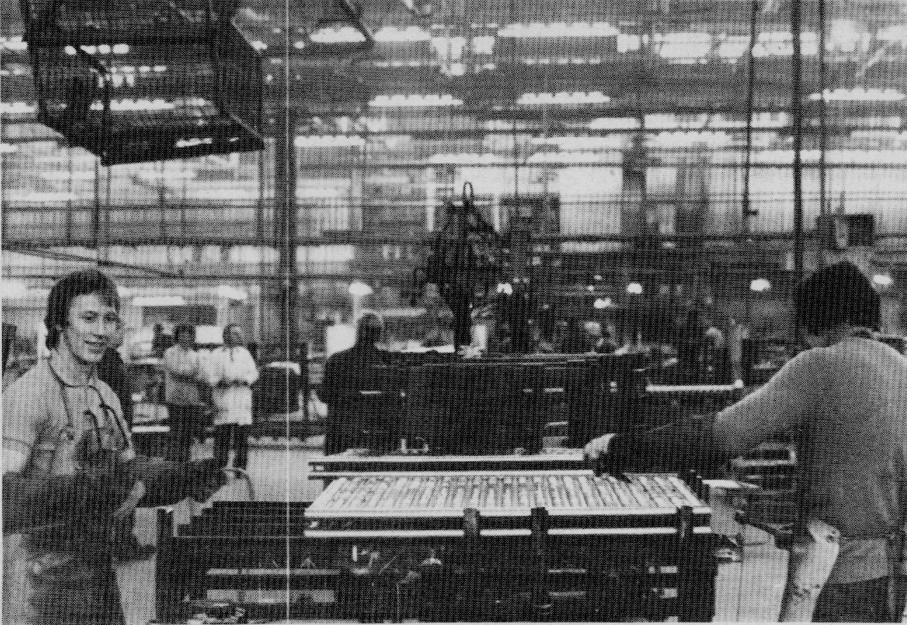

Radiators in production

An automatic press in operation

0 Comments