One artist who embodied the rebellious spirit of Liverpool — probably more than anyone else — was Arthur Dooley (1929–1994), a self-taught sculptor whose work brought him fame but not fortune. Dooley was a kind of lovable eccentric, pot-bellied, fond of a drink, hopeless at managing his money and the archetype of a bolshie Scouser.

Arthur Dooley at work

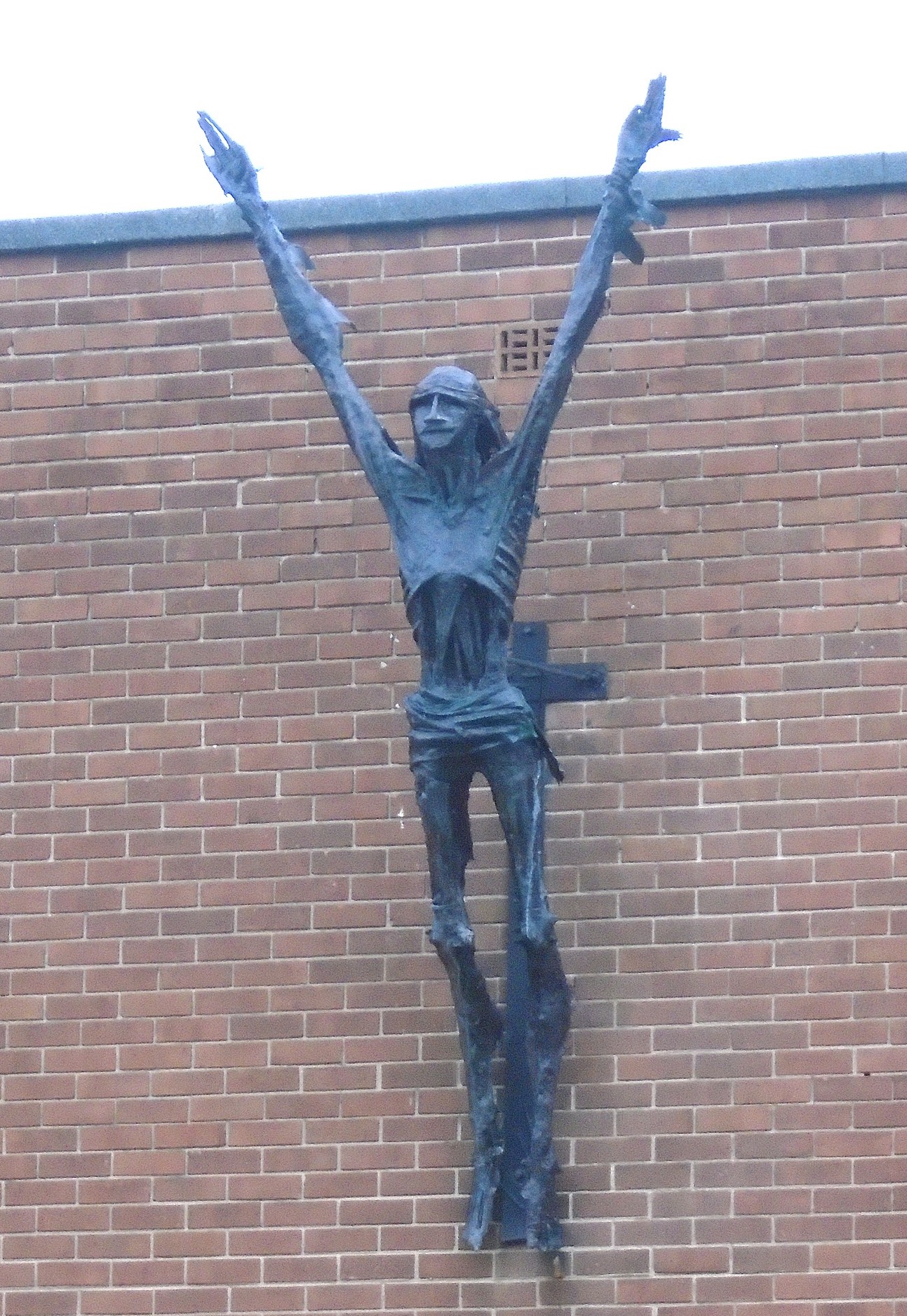

A Communist and a devout Catholic, he had left school at 14 and got a job as a welder at Cammell Laird’s shipyard in Birkenhead. The welding skills proved useful later because his sculptures were mostly made from scrap metal. One of them was a 12-foot sculpture outside a church in Toxteth, a multi-ethnic district of the city. It was said to have caused much controversy when first unveiled in 1967: a black metal and fibreglass figure of ambiguous ethnicity attached to the side of the church. Dooley had titled it “The Resurrection of Christ” but it immediately became known as “The Black Christ”.

The “Black Christ” sculpture

In an unusual protest in 1968 Dooley and two other artists rode through the city centre on horseback and up the steps of the Walker Art Gallery. They were complaining about a lack of local artists in its collection and the high fees charged by another gallery for putting on exhibitions.

He also objected to questions on the 1971 census form and his public refusal to fill it in resulted in him being fined.

Most of Dooley’s commissioned work was for churches, though he later sculpted a tribute to the Beatles near the site of the famous Cavern Club where the group performed in their early days (the club itself had since been compulsorily purchased and demolished to make way for a project that never materialised). Dooley’s sculpture consisted of a Madonna, not with the baby Jesus, but with four small infants: John, Paul, George and Ringo. Considering that John Lennon had once claimed the Beatles were more popular than Jesus and that rock music was replacing Christianity, the sculpture might have been seen as sacreligious but it soon became a tourist attraction.

One of Dooley’s works which proved too subversive to be completed was a memorial marking the hundredth anniversary of the Manchester Martyrs — three Irish republicans executed for murder in 1867 after killing a police officer (apparently unintentionally). The sculpture had been commissioned by the Connolly Association — named in honour of James Connolly, a republican executed by the British in 1916 for his part in Ireland’s Easter Rising. The sculpture project was eventually abandoned amid political objections but a small mock-up of Dooley’s design survives.

Dooley’s model for the Manchester Martyrs sculpture

In the 1970s he designed a monument dedicated to the 534 British volunteers from the International Brigade who had died fighting fascism in Spain. Located in Glasgow, it carries an inscription saying “Better to die on your feet than live forever on your knees.”

The International Brigade monument in Glasgow

Another of Dooley’s creations (now lost) was the Speaker’s Platform installed at the Pier Head in 1973 — a place where mass meetings often took place. Made of steel and painted a bright socialist red, its shape was inspired by Vladimir Tatlin’s 1920 design for a 400-metre tower as a monument to the Third International. It would have been taller than the Eiffel Tower but was never built because at the time post-revolution Russia couldn’t spare the steel.

The Speaker’s Platform before its removal from the Pier Head

In 1990 Dooley’s much smaller structure in Liverpool, which had been commissioned by the Transport and General Workers Union, was quietly quietly dismantled during renovations at the Pier Head. Its parts were transferred to a council depot in Calderstones Park and later disappeared.

Removal of the podium was viewed by some as an attack on free speech and in 2021 a new red-painted structure designed by a local architect and incorporating a giant-sized copper megaphone was installed at the Pier Head as a tribute to Dooley’s original platform.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Most of Dooley’s sculptures are on display in Liverpool at various locations and an online guide by Laura Higgs tells where to find them.

The Arthur Dooley Archive at Liverpool John Moores University contains project files, exhibition files, sketches and blueprints for sculptures/work, personal records, correspondence, photographs, press cuttings and oral history interviews stored in 38 boxes.

VIDEO: Arthur Dooley meets Bill Shankly (1972)

UPDATE

Lois Keidan has sent us this photo of her younger self with a goat sculpted in scrap metal by Arthur Dooley. “My parents were fans of Dooley but I’m not sure where and when they bought it,” she said. “The subject is unusual for him but the materials are his signature use of found stuff.” [Added 27 April 2025]

There is an Arthur Dooley museum inside his old workshop in Seel Street which is worth a visit .