by DAVE WARD

It was the long hot summer of 1976. Dave Calder, Libby Houston, Carol Ann Duffy and I had been invited by Dave Rickus of Merseyside Play Action Council to run poetry workshops on the summer playschemes. But how to create a space for children to sit down and write quietly when all around was the bustle and noise of everyone else playing games … running, jumping, shouting and laughing? The answer was simple – make another game!

I had already worked at Great Georges Project, the converted Congregational chapel at the edge of China Town – its soot-stained walls and pillars giving it the nick-name of ‘The Blackie’ (now renamed The Black-E). Here games that combined skill and chance were used as a starting-point for making art.

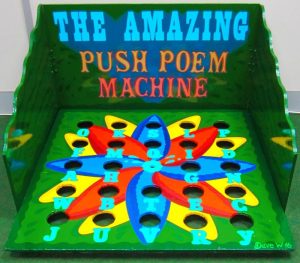

‘The Amazing Push Poem Machine’

My own contribution was to set out the letters of the alphabet and invite participants to throw a small beanbag. Wherever it landed, they’d add a word to their poem beginning with that letter.

Calder and Rickus said it needed to be bigger, better, brighter, so they built a ramp with broad fairground stripes for a ball to bowl up, then bounce around to land in a lettered box. Carol Ann dubbed it The Amazing Push Poem Machine and in the Bronte Centre, close by the old Bull Ring tenement block, poems emerged:

JUMPING WHALES TUMBLING CHEERFULLY

WALLOWING IN WATERPEOPLE RAN GREATLY DISAPPOINTED, SAD

FRANK IS DRUNK AND YET LOST

and from one four-year old girl …

UNDER BUMBLE BEE

F- OFF ROSY

When the poets returned the following summer, they were amazed to be greeted by children quoting their lines from the previous year!

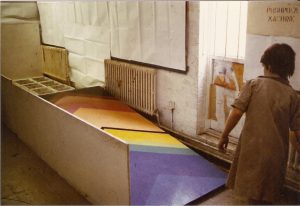

An early version of the Amazing Push Poem Machine

A more recent version of the Amazing Push Poem Machine

At Rice Lane Playscheme, The Amazing Push Poem Machine was combined with Wendy Harpe and volunteers from Great Georges Project to create a picnic of poems with letters sculpted from toast, celery and sausages, laid out on cloths spread across the grass:

MICE BEGIN A GAME

ROLLING MERRILY HOME

FALLING OUT OF TREES

BANGING ON THE GROUND.

Dave Calder and I continued: each year more games – ‘Amazing Animals’, ‘City of Poems’, ‘Elemental Poetry’ – more playschemes, more poems, more poets. Richard Hill, Matt Simpson, Alan McDonald, John Hughes, Kevin McCann, became involved, along with visitors Tina Fulker, Alan Jackson, Pete Morgan.

The Windows Project was now established and we moved on from the random-word generator of The Amazing Push Poem Machine to encouraging participants to write about what was going on around them, their thoughts, their feelings, their lives – as well as delving into their imaginations for crazy creatures, wild fantasies and dreams.

But why ‘Windows’? After leaving Great Georges Project, I moved to Halewood – then an overspill housing estate on the edge of the city – and became involved with The Halewood News, a community newspaper produced by Halewood Community Council and distributed free to every household. When word got round that I was a poet, I began to be approached by others on the estate who wrote poetry as well. Using the Community Council’s large Roneo duplicator, a magazine was produced of poems, stories and artwork: Arthur’s Colour Supplement (‘Arthur’ was the mysterious silhouetted logo on the mast-head of The Halewood News).

Then, as part of the Halewood Festival, the poets – all local residents, including internationally-celebrated Matt Simpson, along with Icilda McLean, who was working as a dinner lady, and biker Frank McDonald – joined forces with local musicians to create a multi-media show staged at Bridgefield Forum. But the show needed a title. “Let’s call it ‘Windows’” said Matt. ‘Windows’ was the title of one of Icilda’s poems:

‘Big ones, little ones, all in a row.

Sun shining down on them makes them all glow…’

The name stuck. The idea of poetry and music in Halewood stuck as well and continued with regular nights in Halewood Library, attracting a local audience as well as people travelling from all over Merseyside. With funding from the National Poetry Secretariat, ‘Windows’ was able to invite nationally-known guests, including Cumbrian poet Norman Nicholson, Brian Patten, Adrian Mitchell, Libby Houston, Pete Brown (famed as lyricist for rock band Cream) and many more. ‘Windows’ ran for ten years, in the Library and then in Halewood Community Council’s new Derrick Adams Youth Activities Centre.

And those Windows nights gave the name to The Windows Project, which continued to grow, involving more and more poets including Levi Tafari, Mohammed Khalil Eugene Lange, and John Walsh – running workshops in youth clubs, libraries and schools.

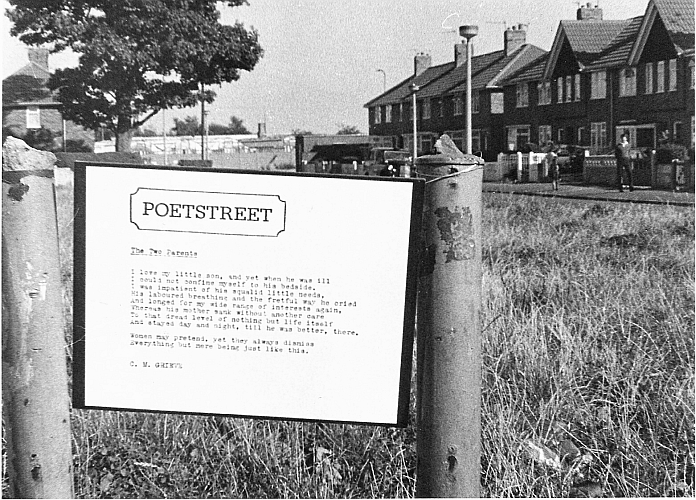

In 1983, Dave Calder and I devised ‘poetstreet’. Eighty-three streets with names that happened to match the surnames of contemporary poets, were selected across Liverpool and Birkenhead. Poems by those poets were typed, photographed, enlarged and mounted on boards, using facilities at Colin Thomas’s Aware Photographic Workshop in Lark Lane. Dave Calder and I then drove around the streets, installing the poems on lampposts or walls, photographing them, then moving on to the next. Some of the boards were seen to be still in place two weeks later!

In selected streets, unsuspecting audiences numbering from one to twenty were given live readings of work by the appropriately named poets: Richard Hill on Hill Street, Alasdair Paterson on Paterson Street, Dave Calder on Calder Drive and myself on Ward Street.

Serving up poems in cafes

A further piece of ‘guerrilla poetry’ was ‘menu’ – in collaboration with independent cafes: Tabac on Bold Street, Keith’s in Lark Lane, Ananda Marga on Hardman Street, The Armadillo on Mathew Street, as well as The Lyceum at the bottom of Bold Street.

Windows Project poets became ‘waiters’ for the day, offering menus of word games, including the invitation to write your own poem, or to have a poem read to you at your table. The tables themselves were dressed with cloths covered with lines from poems, or chequered patterns and black-and-white blocks which could be moved about or stacked to make new designs. The blocks were created by sculptor Pete Hatton, who also contributed a life-size dummy ‘customer’ who would lurk in the corner of each café. Dave Gollancz recorded customers’ poems to edit into a tape montage.

At lunchtime in Ananda Marga we encountered Neil Oram, playwright, and Ken Campbell, who was directing Oram’s play-cycle The Warp at The Everyman Theatre. They kept us busy, requesting more and more poems, well into the afternoon! At that time, not only was Campbell director of The Everyman, but Bill Harpe (Great Georges Project) had been elected to the Chair of Merseyside Arts Association and Jeff Nuttall was Head of Liverpool Art School.

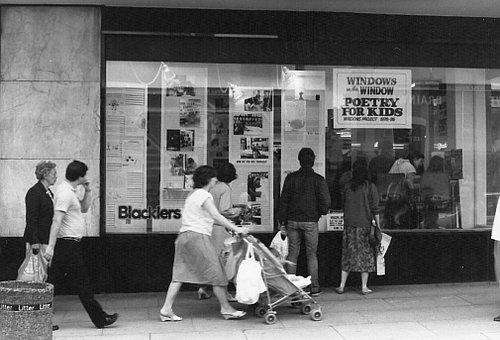

Poetry on display in the window of Blacklers store

I had previously collaborated with Dave Calder at Great Georges Project to put on a series of poetry events with specially created ‘environments’ by sculptor Roland Shannon. These included a blacked-out room for Jeff Nuttall with bones hanging from the ceiling. The bones had been collected from an abattoir, boiled in an oil drum in the Nelson Street gulley, then painted pastel shades. The event began with Jeff Nuttall outside the room knocking loudly on the door but he didn’t realise it was glass painted over, and his fist went straight through. He careered into the room, wearing only a shirt, with blood dripping from his wrist.

Other environments included a throne in the shape of a lily for Libby Houston and hanging strips of newsprint, through which an old black-and-white film was projected, for concrete poet and sound artist Bob Cobbing.

SMOKE magazine

Following the success of Arthur’s Colour Supplement, I used the facilities at Halewood Community Council to produce SMOKE magazine, with contributions from local, national and international poets. Early issues included Miroslav Holub, Barry MacSweeney and Tom Pickard. The first four issues were printed on the Community Council’s Roneo duplicator. Production then switched to offset litho at Halewood Job Creation Scheme.

The first issue of SMOKE magazine

Later, SMOKE was printed at Ananda Marga, on a large press in the basement of their health food shop and restaurant on Hardman Street. Circulation peaked at 1,500, and copies were sold around pubs and bars: The Everyman, Philharmonic, Cambridge, Ye Cracke, Kirklands and The Grapes/Peter Kavanagh’s. I recall a conversation in Peter Kavanagh’s where a customer told me: “This town is going to go red – you know what I mean?’” It was the night before the start of the conflicts with the police in Toxteth in 1981.

The readings in Halewood were part of a network with regular poetry nights at Sampson and Barlow’s restaurant on London Road, the Why Not? on Harrington Street, The Gazebo café-bar at the bottom of Duke Street and O’Connor’s Tavern on Leece Street – variously hosted by Dave Calder, Mike Hart, Harold Hikins, Sylvia Hikins, Syd Hoddes and Jim Blackburne. As well as regulars, all offered ‘open floor’ spots where anyone could get up and read. This followed on from sessions in the Sixties led by Brian Patten, Roger McGough and Adrian Henri in the Everyman basement, Chauffeurs Club and elsewhere.

The Windows poetry and music group performed at the opening of Colin Thomas’s exhibition of black-and-white images of the Halewood estate, for which he was awarded a Kodak Bursary. This was the first exhibition at Merseyside Visual Communications Unit (later to become Open Eye).

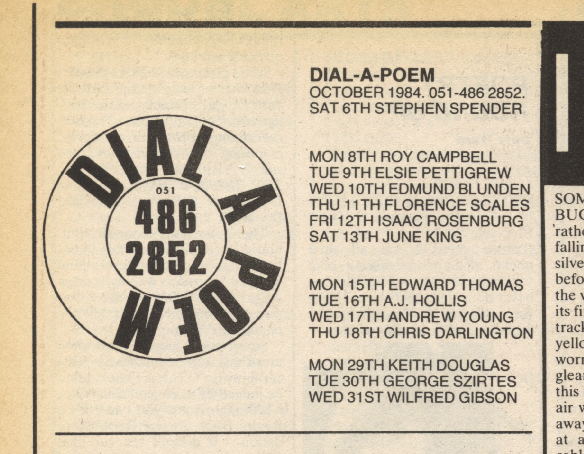

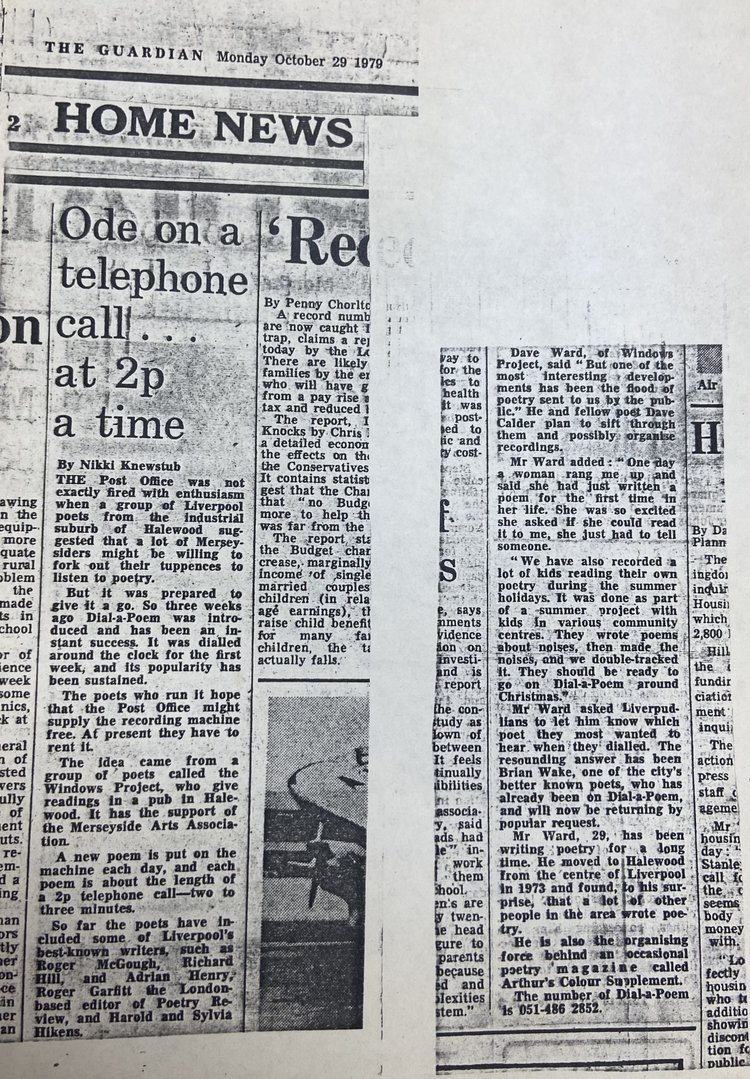

Dial-a-Poem

For ten years through the 1980s, The Windows Project ran Dial-a-Poem, the longest-running such scheme in the country. All the poems were pre-recorded on reel-to-reel tapes, using a Uher portable machine. We then transferred single poems on to telephone answering cassettes which had the capacity for three-minute out-going messages. To begin with we put up a different poem every day, later changing to one a week.

Dial-a-Poem’s schedule for October 1984

The answering machine was located in my bedroom and it was not unusual to be woken in the early hours of the morning by the click and whirr of the tape as someone rang in to hear poets as various as Norman Nicholson, Thom Gunn and Pete Morgan, alongside poems from local writers’ groups and readings of favourite poems from the past. Dial-a-Poem attracted media attention, including interviews for BBC Radio 2 and 4 and a cartoon in The Daily Mirror: “Shsh Mr. Shakespeare is listening to Dial-a-Poem”.

An article about the Dial-a-Poem scheme published in The Guardian, 1979. [Open image in new tab to enlarge]

The Windows Project still continues, with plans to celebrate fifty years in 2026. But these first two decades laid the foundations – with the idea of making writing an everyday activity, accessible to all.

Dave Ward is a poet and short story writer for children, young people and adults. He has been leading workshops in schools and the community since 1971 and in 1976, together with fellow poet Dave Calder, he founded the Windows Project.

I remember Windows really well and the Smoke magazine. Although I never contributed I admired the work Dave Ward did and it’s great to see that it’s still going.