.

Government inspectors issued a confidential — and scathing — report on the Scotland Road Free School just a few months before it closed, Liverpool People’s History has discovered.

The inspectors visited on six days in June and July 1973, as a long-running dispute between the school and the council’s education committee was coming to a head. Between the inspectors’ visits and the delivery of their report seven weeks later, the education committee ordered the school to leave the council-owned premises it was using.

By that stage, what had begun two years earlier as a bold attempt to revolutionise teaching methods was clearly on the brink of collapse and the inspectors’ report – in eight pages of single-spaced typing – gave a devastating picture of the school in its death throes.

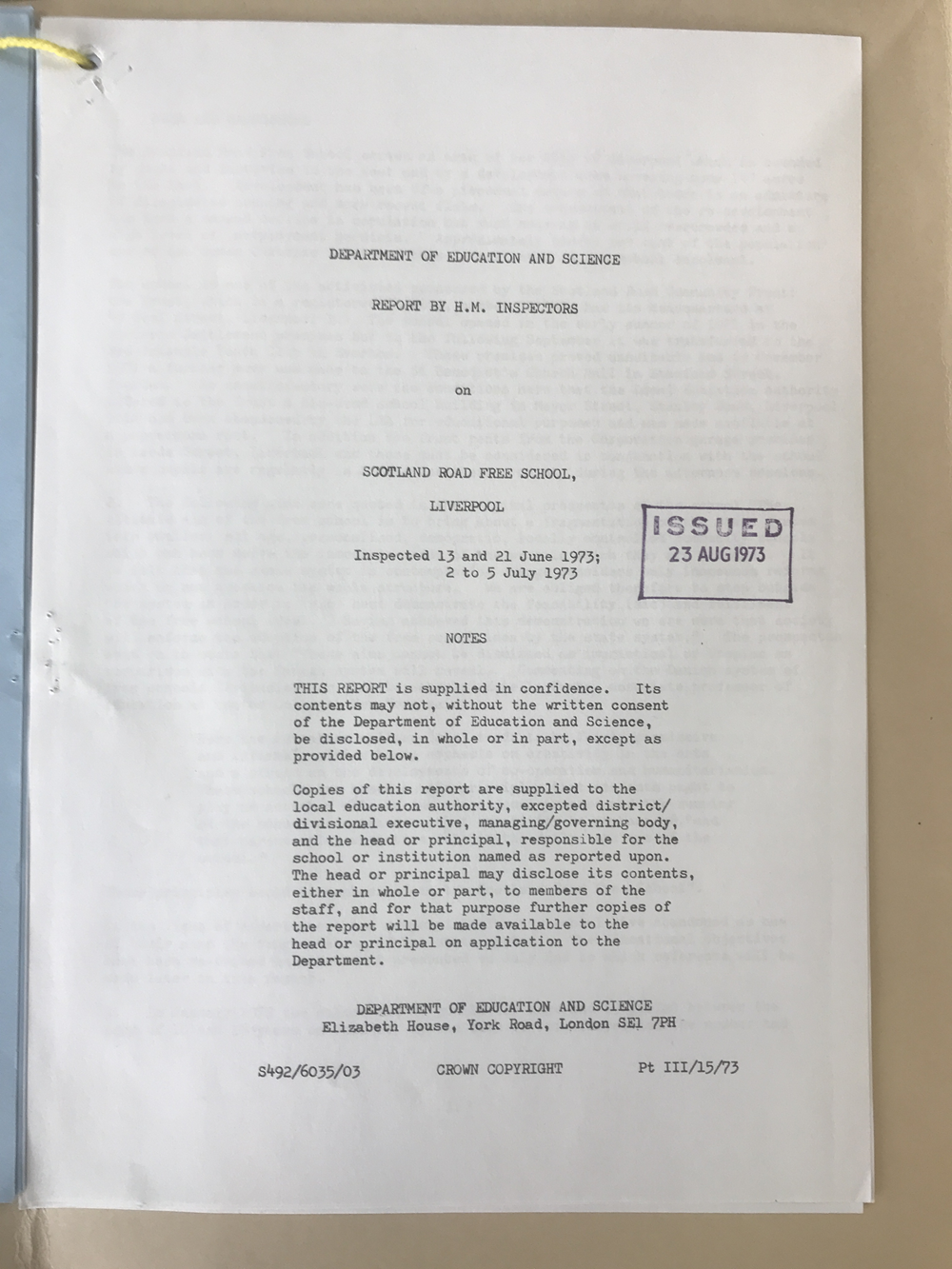

Circulation of the report was strictly controlled and consequently very few people appear to have known about it at the time. One copy was sent confidentially to the local education authority and another to the “head or principal” of the Free School. A note on the cover warned that its contents must not be disclosed “in whole or in part” without written permission from the Department of Education and Science in London. The note also implied that the report should not be photocopied: if the Free School wished to inform staff about its content further copies would be made available “for that purpose” on application to the Department.

Years later, however, those restrictions are gone and the report can be read by anyone wishing to see it. A copy is preserved in the National Archive at Kew — where Liverpool People’s History found it recently.

Background to the report

The inspectors’ report is reproduced in full below but it’s important to view it in context. Although the inspectors saw the school as having little educational value many of the problems they highlighted – such as the appalling state of its premises and frequent changes in its unpaid staff – were due to factors outside the school’s control. They can be attributed to a lack of funding coupled with minimal support from the authorities.

Readers may also find it interesting to compare the inspectors’ view with more sympathetic (though not uncritical) views from former pupils and teachers quoted in an earlier article by Liverpool People’s History.

Opened in 1971, the Scotland Road Free School was a radical and ultimately doomed attempt to develop new ways of learning and a different kind of relationship between teachers and those they taught. Students could choose when to attend the school and what to do when they got there: the onus was on teachers to make classes interesting enough for them to turn up.

These ideas were anathema to educational traditionalists and led to much wrangling within the council’s education committee over what support — if any — should be given to the school.

One argument in favour of support was that when children transferred from state schools to the Free School the education authority saved money by having fewer children to provide for. The Free School also benefited the state system because of its willingness to accept “problem” children — and in some cases this saved the authorities the expense of placing them in care or an Approved School.

From the beginning the school had struggled to find suitable accommodation and during its short existence it operated from four different locations in quick succession. By the spring of 1972 it was based at St Benedict’s church hall in Stanfield Road — a building that Liverpool’s Director of Education, C P R Clarke, described as “completely unsatisfactory for the purpose of education”.

Clarke informed the committee: “Everywhere is dirty squalid dark dismal and cold … Toilet provision is abominable. A satisfactory mid-day meal is provided but arrangements for eating are unhygienic.” His report added that the school lacked materials for reading and writing, and little “purposeful or profitable” activity was taking place: “Such a school must be well-housed and well equipped and must have a definite educational programme.” (Daily Post, 12 April 1972, page 9)

The education committee’s first response was to support a call for Margaret Thatcher (then Education Secretary) not to recognise the Free School but this was later challenged by Labour councillors. Among them, Bill Lafferty pointed out that many of the problems identified by the education director were due to the committee’s own refusal to provide adequate accommodation.

This prompted the committee to offer alternative premises: Stanley School on Major Street — a former Special School built in the 19th century. It wasn’t much of an improvement on the church hall. The inspectors noted that it had no fire safety certificate and one councillor openly wondered who would be legally responsible “if the roof fell in” (Daily Post, 21 March 1973, p7).

The council offered the building at a peppercorn rent of £1 a year but in addition it wanted the school to pay rates (the property tax collected by local authorities at the time). The council was also demanding £495 — money said to be owed mainly for school meals (which other schools didn’t have to pay for).

The Free School duly moved into the building but the lease remained unsigned — apparently because the school was holding out for better terms. The council agreed to waive the £495 but it seems the school was also seeking a grant from the council to cover payment of the rates (Daily Post, 17 July 1973, p7).

At this point the committee lost patience and issued the school with notice to quit. The school replied that it was determined to stay and began lobbying councillors to reverse their decision. The school’s co-founder, John Ord, said: “We are determined to tell them that this place is not as bad as it is painted and we will insist that it is given help and financial assistance and that the council recognises its responsibilities.” (Daily Post, 26 July 1973, p3)

To make matters worse, a group of angry residents complained about a twice-weekly disco held in the school. “The kids come out late at night and then just run wild. They have smashed windows the area and done all sorts of damage,” one told the Daily Post.

Ord replied defiantly: “We shall not be closing down the discotheque even though the majority of people here want us to. It is true that the kids who come to it have been banned from other clubs but there is nowhere else for them to go and this is why we shall keep running it.” (Daily Post, 8 August 1973, p3)

The disco also figured in the inspectors’ report, in connection with school attendance records. The Free School’s “come when you want and do what you like” policy meant that pupils were marked as attending so long as they showed up at some point during the day (or night). The inspectors were not impressed to discover that attendance at the evening discos was being counted as attendance at school.

The report commented:

“Although the school hopes, by its policy of non-compulsory attendance and freedom of choice of activity, to minimise truancy there is evidence to suggest that it is not achieving its aim. Despite the liberal recording policy the average attendance each day would not seem to exceed 56% of the pupils enrolled. This is a significantly lower attendance figure than that which obtains in the nearby secondary schools.”

Failing educationally

The inspectors made some allowances for the school’s experimental nature but concluded it was failing educationally even when judged according to the goals it had set for itself.

The report acknowledged, for example, that out-of-school visits — a major feature of life at the Free School — could help to broaden a pupil’s experience but said their educational value was marred by inept planning:

“No recorded information was available which would indicate a systematic programme of preparation for, or evaluation of, the experiences and impressions gained by the pupils, nor was any discussion heard between staff and pupils relating to the visits.”

The report concluded:

“There is little to indicate that the school is assisting its pupils to develop powers of concentration and sustained effort, or to develop their latent skills … It is said that many of the pupils have deprived backgrounds and that the quality of their lives needs enrichment, but it is difficult to understand how the experiences and environment offered by this Free School are helping to make-up for these disadvantages.”

Less than a month after the inspectors issued their report a single-paragraph news item in the Daily Post announced that Ord — one of the school’s two key figures — had resigned (Daily Post, 20 September 1973, p1).

A last-ditch move to save the school came in late November when Liberal councillor David Alton told the education committee a group of community organisations was offering to take over tenancy of the building and keep the school going, but this was rejected by 17 votes to three (Daily Post, 28 November 1973, p7).

The Free School finally closed on 11 January 1974 — which left the council struggling to find other schools willing to accept its former pupils.

* * *

The inspectors’ report: full text

1. AREA AND BACKGROUND

The Scotland Road Free School serves an area of the City of Liverpool which is bounded by docks and factories to the West and by a development area covering some 147 acres to the East. Development has been of a piecemeal nature so that there is an admixture of dilapidated housing and more recent flats.

One concomitant of the re-development has been a marked decline in population but much housing is still overcrowded and a high level of unemployment persists. Approximately ninety per cent of the population are of the Roman Catholic faith and this is reflected in the school enrolment.

The school is one of the activities sponsored by the Scotland Road Community Trust: the Trust, which is a registered Charity, number 501952, has its headquarters at 49 Seel Street, Liverpool 1. The school opened in the early summer of 1971 in the Victoria Settlement premises but in the following September it was transferred to the Red Triangle Youth Club in Everton.

These premises proved unsuitable and in November 1971 a further move was made to the St Benedict’s Church Hall in Stamford Street, Everton. So unsatisfactory were the conditions here that the Local Education Authority offered to the Trust a dis-used school building in Mayor Street off Stanley Road, Liverpool. This had been abandoned by the LEA for educational purposes and was made available at a peppercorn rent. In addition the Trust rents from the Corporation garage premises in Leeds Street, Liverpool and these must be considered in conjunction with the school since pupils are regularly in attendance there — mainly during the afternoon sessions.

* * *

2. The following aims were quoted in the original prospectus of the school: “The ultimate aim of the free school is to bring about a fragmentation of the state system into smaller, all age, personalised, democratic, locally controlled community schools which can best serve the immediate needs of the area in which they are situated. It is felt that the state system in contemplating change considers only innocuous reforms which do not question the whole structure. We are obliged therefore to step outside the system in order to (sic) best demonstrate the feasability (sic) and fulfilment of the free school ideal. Having achieved this demonstration we are sure that society will enforce the adoption of the free school idea by the state system.”

The prospectus went on to state that “These aims cannot be dismissed as impractical or Utopian as comparison with the Danish system will reveal. Commenting on the Danish system of free schools (Friskoler) or “little schools” Estelle Fuchs, associate professor of education at Hunter College, New York said:

“Here the education millieu (sic) tends to be fairly permissive and informal, with a heavy emphasis on creativity in the arts and a stress on the developments of co-operation and humanitarianism. These schools are based on the principles that students ought to play as active a role in the educational process and the running of the school as a teacher, that creativity be emphasised, and that parents play an active role in the daily workings of the school.”

These principles would be emphasised in the Scotland Road Free School”.

In the light of experience those responsible for the school have abandoned as one of their aims the fragmentation of the state system. The educational objectives have been re-stated in a document presented on July 2nd to which reference will be made later in this report.

* * *

3. In January 1972 the school had 47 pupils (28 boys and 19 girls) between the ages of 10 and 16 years on roll but by the time of this inspection the number had increased to 94 on June 21st as illustrated in the following table:

In addition a number of children under 5 years of age attend at the school. It is unusual for more than 5 of these young children to be present but they are not recorded in any register. Although an application has been submitted for registration as a play group the shared use of premises and facilities would indicate that this unit should be regarded as an integral part of the school.

An examination of the register on July 2nd indicated that during the week beginning June 25th, 5 pupils were excluded from the school for previous non-attendance over a considerable period. They were 3 boys of 13, 14 and 15 years respectively and 2 girls each of 15 years of age.

There would seem to be some inconsistency in this policy since the register (which has only been maintained in its present form since June 4th 1973) indicates that 24 pupils had not attended at all during the currency of the register. Again it would seem to be opposed to the general philosophy of the school. An analysis of the register gives the following attendance figures between June 4th and June 29th. Maximum number of attendances: 36 (two days were recorded as official holidays — Corpus Christi and St Peter and St Paul).

One boy was recorded as being in care and is not included in the above totals. It must also be emphasised that it is the school’s practice to record an attendance no matter how brief a period a pupil spends in school so that for many pupils actual attendance in school for a significant period of the day is very limited indeed.

The school states that a pupil’s presence at an evening discotheque is regarded as an attendance but this is difficult to accept since an admission charge is levied — even though remissions are made in some cases. Although the school hopes, by its policy of non-compulsory attendance and freedom of choice of activity, to minimise truancy there is evidence to suggest that it is not achieving its aim.

Despite the liberal recording policy the average attendance each day would not seem to exceed 56% of the pupils enrolled. This is a significantly lower attendance figure than that which obtains in the nearby secondary schools. Two additional points give cause for concern in the registration practices of the school:

a. The failure to ensure that all pupils are recorded in the register. Two pupils of 11 years and 12 years who have attended at the school for approximately 2 months and 4 months respectively have not yet been entered in the register.

b. The register is not completed at the opening of each session and during the week beginning July 2nd no attendances had been registered by the close of the afternoon session on July 4th. No admission register had been maintained when HM Inspectors visited the school on June 13th but following advice a rudimentary register has been begun but still lacks many of the essential details.

* * *

4. No fees are charged and the only payment made by pupils is that for the mid-day meal when a charge of 5p is made. In cases of hardship even this charge is waived. The meal is cooked and served on the premises and is available to the pupils of the school and to members of the local community, mainly old-age pensioners, but also to some unemployed men and a number of boys who are said to be truanting from maintained schools. It would seem that some of the enrolled pupils attend only for the meal. The nursery children eat in their own room, the pupils and young adults in the hall, and the old-age pensioners in the “sitting-room”.

Attention must be drawn to the need to maintain higher standards of hygiene than those which prevail at present.

* * *

5. The buildings which the school now occupies once served the Local Education Authority as a Special School. They were built in the late 19th century with some additions in about 1910.

Outdoors there is a hard-surfaced area of limited extent which is rarely used, and at the time of these visits was littered with charred furniture, baulks of timber, broken glass, garbage and rubbish of many kinds. Some of this was removed during the week beginning July 2nd. The outdoor sanitary facilities comprise 4 WCs and a urinal for the boys and 6 WCs for the girls. They were in such a noisome condition and so littered with rubbish, broken slate and glass as to be quite unusable although a start was made on cleaning them on July 2nd.

Indoors the accommodation is arranged on 3 floors and provides very generous space for the numbers enrolled. In the basement are 2 adult size WCs, two wash-basins and an earthenware sink, a room in which are stored crates of empty bottles and beer kegs, and a large windowless area containing much combustible material.

On the ground floor are a hall, a room which functions as a nursery, a “sitting-room”, a kitchen, and an office with an adult size WC and a wash-basin adjacent. The office is still in process of being re-furbished following a fire and much material is stored here in a most untidy manner.

On the upper floor are 5 large rooms, two with fitted laboratory-type sinks, and 2 further wash-basins are located at the head of the stairs. In every case WCs and wash basins are in an unacceptable condition of cleanliness. There is no hot water at any of the wash-basins owing to a fault in the heating system and there is a general lack of soap and towels.

Although the building and its fixtures offer considerable potential for creating a learning environment with some aesthetic quality to offset the reputed drab environments from which the pupils come little has been achieved in this direction. The rooms are largely gaunt shells often garishly painted and the furniture which is available — some old school desks, a few old woodworking benches, discarded wall seats, and a motley collection of old, dilapidated easy chairs and settees — does not serve to enhance the appearance of the premises. When to this is added the results of extremely casual caretaking and deplorable standards of tidiness the aesthetic appeal of the school is abysmally poor.

No cloakroom facilities are available at any point in the premises and very few electric sockets are provided with bulbs; in the basement the staircase and the space to which it gives access, and one WC lack artificial lighting, while on the ground floor artificial lighting is inadequate in the nursery which has only one electric light bulb and in the large sitting-room where there are 2 bulbs. The staircase leading to the first floor is without artificial lighting as is the room at the head of the stair-case. Two other rooms on this floor, the woodwork and art rooms, also lack electric light bulbs.

The garage at Leeds Street, which serves both general community and educational purposes, is a scene of great confusion and disarray and is full of vehicles in — every state of repair or dismantling. The accumulation of scrap engines, discarded cooking stoves, caravans and boats in process of renovation, mechanical equipment, in addition to welding and oxy-acetylene equipment raises grave doubts as to the safety of pupils when in attendance.

On June 13th 3 boys between the ages of 11 and 15 years were observed using welding equipment in this large garage without supervision. They had not been given a set task but had decided of their own volition to use the equipment. It is not surprising that the lack of supervision and guidance had resulted in the activity becoming less purposeful than it might have been with a consequent increase in the degree of hazard to which pupils were exposed. No usable sanitary facilities are available at these garage premises but the materials necessary to repair the water system are now said to be available.

* * *

6. The fire prevention officer has not issued a certificate of satisfaction relating to the school premises.

* * *

7. Not only is equipment woefully meagre even to support the unusually restricted educational programme but there are virtually no resources of any kind to enrich the educational visits on which the school places such emphasis. Such tools as have been acquired recently are not wholly appropriate to the needs of the pupils and the safety aspects of their use have not been adequately considered.

The few books which are available are, in the main, appropriate to children of primary school age. Although most of the pupils are of secondary school age it must be acknowledged that the levels of attainment of some pupils justify the selection and use of some books of this level of difficulty but for many of the others there is little to interest or challenge them. The school regards the whole community, both in the immediate locality and further afield, as its classroom. If this experience-based learning is to he effective there is a great and urgent need for a wide variety of books, maps, materials, equipment and tools to supplement and re-inforce the first-hand information which could be acquired in the field.

* * *

8. HM Inspectors experienced some difficulty in obtaining precise information relating to the staffing of the school but observation and discussions suggest that there are 13 men and women who are associated with the day to day functioning of the school, either by way of administrative responsibilities, or involvement in the educational and/or social aspects of the school’s work. Their qualifications for the work vary widely; two are graduates with teacher training, four are graduates and one a qualified teacher while the rest are without professional qualifications. None is paid for work in the school but some have unem1oyment benefit, and others are in receipt of social security payments.

There is no organised pattern of responsibility for areas of the curriculum, and attendance of individual teachers is irregular, and unpredictable in terms of arrival and departure. Although the the school emphasises that it does not view the curriculum in traditional terms it does suggest that skilled advice and guidance is available to the pupils whenever they should need it. HM Inspectors are quite clear that the irregular and unpredictable attendance of the staff preclude any guarantee of continuity of advice.

Although the three movers in this school movement remain with the organisation one would appear to have withdrawn from the teaching situation; the records submitted by the school show clearly that there have been many and frequent changes among the supporting staff.

A letter written by the school to the Department of Education and Science as recently as May 16th 1973 listed 7 people as being primarily concerned with the educational/social work of the school. By the time of the visit on June 13th two of these had withdrawn from the school and two other individuals had replaced them. This merely reflects what has become a pattern of frequent change.

Staff replacements are not carried out in accordance with any considered policy but are purely fortuitous and the interests of the incoming members(s) unpredictable. This leads to serious deficiencies in the range of specialist advice available to the pupils. It would seem that a significant division has evolved between the main involvements of the 13 individuals connected with the school, and 5 appear to restrict their contribution to either work at the garage or to administrative responsibilities. Only 2 members of staff have been seen to operate in both premises.

* * *

9. The school has now been in being for 2 years and, in common with many other schools, has experienced frequent changes of staff. In addition there has been unusual fluidity in the arrival and departure of pupils. These changes point to the need for careful planning of the school’s work. However the activities would seem to lack any element of forward planning and in consequence it is difficult to discern any educational progression or continuity in the little work recorded by the pupils.

Activities seem to be arranged on the spur of the moment and, although on occasion this is justifiable, and perhaps desirable, it cannot be regarded as an appropriate basis on which to conduct the long term operation of a school if the pupils are to be given the skills, techniques and knowledge to enable them to live on equal terms with their peers.

On July 2nd a document purporting to be a plan of work was made available. This tends to emphasise the aims and objectives of the Free School movement without giving the clear, positive guidance on ways and means of achieving these ends which is so essential when staff membership changes frequently, and when the teaching experience of those in day to day contact with the pupils is limited.

Item B of the document emphasises that “All decisions concerning the future, policies, and activities etc. of the Free Centre will be decided by those who use the Centre i.e. children, parents, teachers, residents”. No organised system of decision making was seen in action although several situations arose when collective discussion and decision making could have profitably occurred. The situation in the school could perhaps best be described as predominantly “do as you please” but on occasion, dictatorial.

Item F specifies the system of pastoral care which is said to operate within the school but discussions with the pupils revealed that they are quite unaware of the identity of the person to whom they might refer in case of difficulty. It is difficult to discern any pattern in the functioning of the school and the individual pupil has complete freedom to choose activity or inactivity and to change at will. The fact that so many choose educational inactivity might be indicative of the needs of many pupils to work within a more organised and systematic framework which would give the sympathetic guidance and support which so many obviously require.

Although attention to the individual’s educational and social needs is said to be a prime porpose of the school those responsible neither assess a pupil’s needs, nor plan for the individual pupil, nor make records of pupils’ progress and achievements. These omissions give no cause for confidence in the school’s educational or social policies.

10. The school has no regular hours of opening and some pupils were seen to wait on the steps for a considerable time before the premises were opened although they had arrived at or before 9.0 a.m. Other pupils arrive during the course of the morning and some appear to time their arrival to coincide with the serving of the mid-day meal and to leave immediately afterwards.

* * *

11. STANDARDS OF WORK

The amount of recorded work available was negligible and that which was seen was in exercise books which had been issued as recently as June 12th; nothing was available relating to the period before this date. In the books examined there was no indication of continuity or progression or of the encouragement of individual skills other than copying.

* * *

12. The work in the Free School is said to be organised on an activity basis in the various rooms. For the sake of clarity it would be advisable to comment on each area seen.

i. The Nursery:- the room which accommodates the nursery group, and the furniture in it, need a thorough cleaning. One door opens on to narrow steps which lead down to a playground. There is much rubbish adjacent to the steps and bad odours occasionally permeate the room from this. There is no sanitary provision near to the room and the children are taken to an adult size WC, access to which is through the office. As this room is full of rubbish and building materials as a result of a recent fire, access to the WC is difficult. The WC and the adjacent wash-basin are not clean and the latter fitment has neither hot water, nor soap, nor towel provision. The youngest child occasionally uses a pot in the classroom but this receptacle is not emptied regularly. No effort is made to implement hygienic social training at any time.

The meal is brought from the kitchen and eaten in the nursery. An effort has been made to provide some play materials but they are poorly displayed and arranged, and only desultory play was observed. The uncertainty and irregularity of the children’s attendance (5 or 6 seems to be the maximum) preclude much development taking place. A boy of junior age, 8 years of age this month, appears to have free run of the nursery but he is not encouraged to become involved with any activity and he is virtually a non-reader.

On two occasions two 4 year old children left the nursery of their own volition and were seen playing in and on a motor car parked outside the school. Effective care cannot be said to be in operation in this section of the school.

ii. The Art Room:- the work in progress involved the use of scrap materials (polythene sheeting, cardboard, leather off-cuts, polystyrene) and paint. The disposition of the materials and the organisation of resources do not encourage the effective use of either time or materials. Little guidance is given to pupils in the exploration of materials and in consequence the pupils’ level of conception in art is unusually naive and more akin to that normally characteristic of much younger children; standards of execution are remarkably crude and lack understanding of the techniques which would enable pupils of secondary age to use the media expressively.

iii. The adjoining area is given over mainly to the use of wood. Little attention is paid either to the discussion and planning of a task, or to learning the effective use of tools, or to the qualities of materials. It is not surprising therefore that the standards of workmanship are unusually rough and lack refinement. Pupils were seen using sharp cutting tools and power drills without supervision and their lack of skill with such equipment indicates that urgent attention needs to be given to instruction in the use of such tools and to the wider aspects of safety. Attention is again directed towards the advice in HMSO pamphlet №53 “Safety in Schools”.

iv. The room which serves as a combined Mathematics and English base is ill-equipped and there is little to interest or stimulate pupils’ interests in these areas of the curriculum. Few pupils choose to occupy themselves with these studies or to work here and the low standards of achievement in speech, writing and mathematics reflect this lack of interest.

v. The only work seen in the Social Studies area during the course of this inspection was the tracing of a crude outline map of the Liverpool area by 4 boys during a short period of a morning session. There was no further development of this theme.

Apart from what is recorded above there was no further work undertaken which related in any way to the normal school curriculum. At no time did HM Inspectors observe any attempt by any member of staff to assist pupils in developing their competence in the basic skills of reading, writing and numeracy.

* * *

13. The school operates a work experience course and 18 pupils were said to be taking part (8 girls and 10 boys). At least 8 of them are below 15 years of age. Visits were made by HM Inspectors to a number of the firms involved when it was learned that some pupils had never taken up the opportunities offered and the attendance of others had been irregular. Nevertheless one or two employers made favourable comments on the work of the pupils they had received. It was also revealed that some were being employed for at least 5 days each week and many were receiving substantial payment.

Conversations with the pupils themselves indicated that in some cases they had left the work which had been paid on a results basis but had been too exacting while in other cases it would seem that the employers had decided to terminate the arrangement. It was not apparent that the scheme fitted into any organised plan of work or had the scheme been submitted to the Local Education Authority for approval as required by the Education (Work Experience) Act 1973.

* * *

14. The philosophy of education which is said to motivate the school emphasises the importance of educational experience beyond the confines of the school. Such educational visits are a proven and well-tried method of broadening a pupil’s experience. It is in this area of work that the school could plan a forward and progressive programme which could provide regular opportunities for the methodical practice and consolidation of the basic skills of reading and writing based on information and experience relating to the visits.

During the period of this inspection the youngest children visited a local park, other groups went to the swimming baths and exhibitions in Liverpool, and 2 major excursions were undertaken — one to witness the launching of a ship and the other to a village in Wales.

Inept planning and bad time-keeping thwarted both these excursions and neither was completed satisfactorily. No recorded information was available which would indicate a systematic programme of preparation for, or evaluation of, the experiences and impressions gained by the pupils, nor was any discussion heard between staff and pupils relating to the visits. The discussions of HM Inspectors with pupils did not reveal that these experiences had been of significance to them.

* * *

15. Some pupils attend the garage at Leeds Street during the afternoons but there is no progressive and continuous scheme of learning. As one pupil remarked “You try to learn by standing around and watching”. Observation indicated that there were long periods when pupils were not even so engaged and in such a hazardous environment doubts must be expressed as to the safety of pupils as indicated in the penultimate sentence of paragraph 5.

* * *

16. Serious administrative weaknesses are apparent in the functioning of this school and the pupils who choose to attend are plunged into an unusually disorganised situation whereas many would profit from a more organised programme of work with the necessary encouragement and sympathetic support.

On the one hand it is possible to commend the easy social relationships which appear to have been established between the older and younger members of this school community; on the other hand it is reasonable to question whether these relationships have ever been put to the test of requiring pupils to carry out specified tasks and to bring them to satisfactory conclusions.

There is little to indicate that the school is assisting its pupils to develop powers of concentration and sustained effort, or to develop their latent skills, or to experience the satisfaction to be derived from planning and carrying out challenging tasks commensurate with their ages and abilities. It is said that many of the pupils have deprived backgrounds and that the quality of their lives needs enrichment, but it is difficult to understand how the experiences and environment offered by this Free School are helping to make-up for these disadvantages.

0 Comments